1. Foundations and Culture

What DevSecOps Really Means

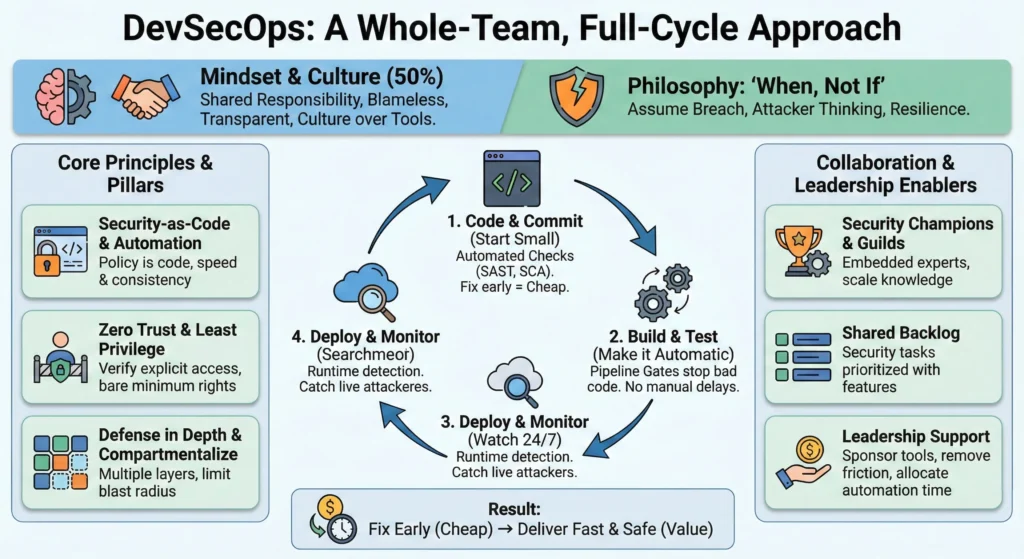

DevSecOps means making security part of the daily habit of writing code, rather than a final exam before release.

Fixing it late is expensive: If you find a security bug after the software is released, it costs more.

Fixing it early is cheap: If you find the bug while you are typing the code, it takes 5 minutes to fix for easily.

No need to do everything at once. Just follow these steps:

- Add tools that automatically check code for basic mistakes (like passwords in plain text) whenever a developer saves their work. This is called SAST (checking the code) and SCA (checking the libraries).

- Make it Automatic don’t let bad code pass. If the security tool finds a big problem, the system should automatically stop the update from going live.

- Once the software is live, use security tools to watch it 24/7 to catch any attackers trying to break in.

1. The DevSecOps Mindset Philosophy Over Tools

DevSecOps is 50% tooling and 50% culture. You can buy the most expensive security scanners in the world, but if your team doesn’t think securely, you will still be vulnerable.

The DevSecOps mindset moves us away from “Security is the Department of ‘No'” to a model where security is a shared responsibility grounded in reality.

1. The Core Philosophy: “When, Not If”

The foundation of the modern security mindset is acknowledging reality. No system is impenetrable.

- Old Mindset: “We must build a wall so high that no one can get in.” (Fortress mentality).

- New Mindset: “Someone will get in eventually. How do we spot them quickly and limit what they can steal?” (Resilience mentality).

2. Pillar I: Assume Breach

Designing systems with the assumption that the network perimeter has already been compromised.

- Zero Trust: – Never trust a user or service just because they are on the “internal” network. Verification is required for every request.

- Defense in Depth: – Don’t rely on one lock. If the firewall fails, the server should be locked. If the server is breached, the database should be encrypted.

- Log Everything: – If a breach happens, you need a trail to understand what happened.

- The Goal: – To minimize the “Blast Radius.” If one container or server is hacked, it should not bring down the entire company.

3. Pillar II: Attacker Thinking (The “Red Team” View)

Shifting from verifying that the software “works” to verifying how it can be “broken.”

Developers usually focus on Use Cases (how a user typically behaves). DevSecOps requires them to also think about Abuse Cases (how a malicious actor behaves).

- Question functionality: “This login form works when I type the password correctly. But what happens if I paste 5,000 random characters into it? Does it crash?”

- Threat Modeling: Before writing code, the team sits down and asks, “If I wanted to hack this feature I’m building, how would I do it?”

- Result: You find design flaws before you write the code, which is the cheapest time to fix them.

4. Pillar III: Principle of Least Privilege (PoLP)

Every user, program, and process should have only the bare minimum access rights necessary to perform its job.

- For Humans: A junior developer does not need “Admin” access to the Production Database. They should only have “Read” access to the Development Database.

- For Machines: A web server needs to talk to the database, but it doesn’t need to talk to the HR payroll system. Block that connection.

- Why it matters: If an attacker compromises an account with “Least Privilege,” they are trapped in a small box with nothing valuable to steal.

5. Reducing Human Error: Automation and Compartmentalization

The philosophy is that humans are creative but unreliable at repetitive tasks. Machines are uncreative but perfect at repetition.

- Compartmentalization: – Break the system into small, isolated chunks (Microservices/Containers). If one chunk is infected, you can cut it off to save the rest.

- Automation as Security: –

- Consistency: – Manual server configuration leads to mistakes (drift). Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC) ensures every server is configured perfectly every time.

- Speed: – Automated patching means you can fix a vulnerability across 1,000 servers in minutes, not weeks.

2. Security Culture – The Human Firewall

Tools can catch syntax errors, but only culture can catch logic errors. Security Culture refers to the shared values, habits, and behaviors of your team regarding security.

1. Shared Responsibility – “Security is Everyone’s Job”

In traditional models, developers built features and security teams found bugs. This created a “Not My Problem” mentality.

- Developers: – Are responsible for the security of the code they write just like they are responsible for performance.

- Operations: – Are responsible for the security of the infrastructure and pipelines.

- Security Team: – Shifts from “doing” everything to empowering others. They provide the tools, training, and consulting.

2. Blameless Postmortems – Psychological Safety

When a security incident happens (and it will), how you react defines your culture. If you punish the person who clicked the link or wrote the bug, you encourage people to hide their mistakes.

The Blameless Philosophy

- The Rule: You cannot fire your way to security. A “human error” is actually a “system error.”

- The Question: Don’t ask “Who broke it?” Ask “How did our system allow this to happen?”

- The Goal: To learn, not to shame. If a developer pushes a secret key to GitHub, the lesson isn’t “Fire that developer.” The lesson is “Why didn’t our git-hooks catch that key before it left their laptop?”

Steps for a Blameless Retro

- Acknowledge the failure openly.

- Investigate the timeline – facts only, no finger-pointing.

- Identify the root cause – process/tooling failure.

- Create action items to prevent recurrence.

3. Transparency and Open Communication

Security through obscurity (hiding details) rarely works. Security through transparency builds trust and speed.

- Internal Transparency: When a vulnerability is found, broadcast it. “Hey team, we found a bug in how we handle tokens. Here is what it was, and here is how we fixed it.” This creates a learning loop for other teams.

- External Transparency: If a data breach occurs, communicating clearly and honestly with customers (rather than hiding it) is essential for maintaining long-term trust.

4. How to Build This Culture – Actionable Steps

1. The Security Champions Program

You cannot hire enough security engineers to sit with every dev team. Instead, identify a “Champion” within each development squad.

- Who: A developer who is interested in security.

- Role: They act as the “satellite” for the security team. They attend security briefings and bring that knowledge back to their squad.

- Benefit: It scales security knowledge without hiring more security staff.

2. Gamification and Reward

Change the incentives.

- Don’t just punish bad security.

- Reward good security: Give out “Bug Hunter” swag, gift cards, or public shout-outs to developers who find and fix vulnerabilities during the design phase.

- Celebrate the “Near Misses”: If someone spots a phishing email, praise them publicly.

Leadership Principles – The Executive’s Role

DevSecOps is a grassroots movement powered by developers, but it is sustained by leadership. Effective leadership in DevSecOps isn’t about enforcing rules. The leader’s job is to clear the path so the team can run fast and safe.

1. Sponsor the Right Tools – Investment

It requires budget. Leaders must treat security tooling as a vital infrastructure investment, not an optional add-on.

- Buy: – Sponsor industry-standard tools (SAST, DAST, SCA) that integrate seamlessly into the existing CI/CD pipeline.

- Developer Experience Matters: – When evaluating tools, leaders should ask: “Does this make my developers’ lives harder or easier?” If a security tool is clunky and slow, developers will find a way to bypass it.

- The Leader’s Action: – Allocate budget specifically for “Security Enablement” tools, separate from general IT costs.

2. Remove Friction – Eliminate “Security Theater”

Traditional security relies on heavy gates manual reviews, Change Advisory Boards (CABs), and long approval forms. This is friction. It slows down value without necessarily adding safety.

- From Gates to Guardrails: –

- Gate (Old Way): “Stop everything. Manual approval for each step of security check.

- Guardrail (New Way): “The pipeline automatically checks if your code meets policy. If it passes, you deploy. No human permission needed.”

- Kill the CAB: Leaders should work to replace manual Change Approval Boards with automated policy checks. If the tests pass, the “approval” is automatic.

3. Enable Automation

Automation requires engineering effort. If a leader fills the roadmap 100% with new product features, the team has zero capacity to build security automation.

- The 20% Rule: – Leaders must protect time (e.g., 20% of every sprint) for “Technical Debt and Tooling.” This gives teams the breathing room to write the scripts that will save them time later.

- Reward Automation: – If a team manually patches a server, say “thanks.” If a team writes a script that automatically patches all servers forever, give them a bonus.

- The Leader’s Action: – When a project is running behind, resist the urge to cut the “security automation” tasks first.

4. Measure Outcomes, Not Outputs

- Bad Metrics (Don’t use these)

- “Number of bugs found”: This encourages security teams to file trivial bugs just to hit a quota.

- “Tickets closed”: This says nothing about risk.

- Good Metrics (Do use these)

- Mean Time to Remediate (MTTR): “When a critical bug is found, how many minutes does it take us to fix it in production?”

- Deployment Frequency: High frequency usually means smaller, safer changes.

- Change Failure Rate: How often do our security fixes break the build?

DevSecOps Principles

The three pillars that hold up the DevSecOps architecture are Security-as-Code, Zero Trust, and Ruthless Automation.

1. Security-as-Code (SaC)

In the past, security policies were written in PDF documents stored on a SharePoint site that developers rarely read. In DevSecOps, policy is code.

You define your security rules using the same programming languages and tools used to build the application.

- Codified Rules: – instead of a manual checklist saying, “Servers must not have port 22 open,” you write a script that checks for open ports.

- Version Control: – Security policies are stored in Git. You can track who changed a policy, when, and why.

- Testable: – You can “test” your security policies just like you test software features.

Example tools: –

- OPA – Open Policy Agent: – A standard for writing policy-as-code.

- Example rule: “Reject any Kubernetes deployment that runs as ‘root’.”

- Infrastructure as Code (IaC) Scanning: Tools like Checkov or Tfsec scan your Terraform/AWS CloudFormation templates to ensure you aren’t accidentally building insecure infrastructure.

2. Zero Trust Architecture

“Never Trust, Always Verify.”

- No Implicit Trust: – Just because a user or service is on the corporate VPN doesn’t mean they are safe.

- Identity is the New Perimeter: – Access is granted based on who you are (Identity), not where you are (Network Location).

- Micro-Segmentation: If a hacker compromises one server, Zero Trust prevents them from moving laterally to other servers because every connection requires a fresh authentication check.

Practical Application: –

- Mutual TLS (mTLS): – Service A cannot talk to Service B unless both present a valid digital certificate.

- Just-in-Time (JIT) Access: Developers request access for 30 minutes to fix a bug, and then access is automatically revoked.

3. Automate Everything

If a task needs to be done more than twice, automate it.

- Speed: – Automation runs in seconds; humans take hours or days.

- Consistency: – A script never gets tired, never forgets a step, and never has a “bad day.”

- Scalability: – You can manually check 5 servers. You cannot manually check 5,000 servers. Automation is the only way to scale security.

Automate: –

- Static Analysis: – Scanning code for bugs every time a developer commits the code using SAST tool.

- Dependency Checks: – Automatically blocking a build if it uses a library with a known virus.

- Compliance Reporting: – Use tools to generate compliance reports automatically from your logs for audit.

Collaboration Models – Breaking Down the Silos

Collaboration Models are the frameworks we use to integrate security expertise directly into the development process. The goal is to move from “Security vs. Developers” to “One Team, Shared Goal.”

1. The Security Champions Program

A Security Champion is a developer (or QA/DevOps engineer) embedded within a product squad who acts as the “voice of security” for that team. They are not full-time security pros; they are developers with an interest in security.

- The Bridge: – They act as the connection between their squad and the central Security Team.

- Responsibilities:

- Reviewing user stories for security risks during planning.

- Triaging security bugs found by automated tools.

- Promoting best practices.

- Training: – The central Security Team provides the Champions with advanced training, “hacker hoodies,” and specialized support.

2. Security Guilds – Communities of Practice

A Guild is a cross-functional group of people who share a common interest in this case, security. It includes the Security Team, Champions, and any interested developers or managers.

The “Guild Meeting”

- Frequency: – Usually monthly or bi-weekly.

- Agenda: –

- Show and Tell: “Here is a vulnerability we found in the Payment Service and how we fixed it.”

- Tool Demos: Showing off a new SAST tool or feature.

- War Stories: Discussing recent industry hacks and how to prevent them.

- Goal: To create a culture of learning and curiosity, rather than compliance.

3. The Shared Backlog

“Security work is just work.”

- Unified Backlog: – Security tickets, technical debt, and new features all live in the same project management board.

- Prioritization: – A critical security vulnerability is prioritized exactly like a critical product bug. It gets a “Ticket ID” and is assigned to a sprint.

- Visibility: – Product Owners (POs) can see the security load. If a team has 50 security tickets, the PO knows they cannot schedule 100% new features for the next sprint.

4. Embedded Security Engineers

For high-risk or core platform teams, a Champion might not be enough.

- Benefit: – They provide deep expertise immediately, without the delay of waiting for an external review.

- The Model: – A professional Security Engineer is fully “embedded” into the squad for a period (e.g., 3-6 months) or permanently.

- Role: – They write code alongside the developers, specifically focusing on security features (encryption, identity management, auditing).

Collaboration Models – Breaking Down the Silos

Collaboration Models are the frameworks we use to integrate security expertise directly into the development process. The goal is to move from “Security vs. Developers” to “One Team, Shared Goal.”

1. The Security Champions Program

A Security Champion is a developer (or QA/DevOps engineer) embedded within a product squad who acts as the “voice of security” for that team. They are not full-time security pros; they are developers with an interest in security.

- The Bridge: – They act as the connection between their squad and the central Security Team.

- Responsibilities:

- Reviewing user stories for security risks during planning.

- Triaging security bugs found by automated tools.

- Promoting best practices.

- Training: – The central Security Team provides the Champions with advanced training, “hacker hoodies,” and specialized support.

2. Security Guilds – Communities of Practice

A Guild is a cross-functional group of people who share a common interest in this case, security. It includes the Security Team, Champions, and any interested developers or managers.

The “Guild Meeting”

- Frequency: – Usually monthly or bi-weekly.

- Agenda: –

- Show and Tell: “Here is a vulnerability we found in the Payment Service and how we fixed it.”

- Tool Demos: Showing off a new SAST tool or feature.

- War Stories: Discussing recent industry hacks and how to prevent them.

- Goal: To create a culture of learning and curiosity, rather than compliance.

3. The Shared Backlog

“Security work is just work.”

- Unified Backlog: – Security tickets, technical debt, and new features all live in the same project management board.

- Prioritization: – A critical security vulnerability is prioritized exactly like a critical product bug. It gets a “Ticket ID” and is assigned to a sprint.

- Visibility: – Product Owners (POs) can see the security load. If a team has 50 security tickets, the PO knows they cannot schedule 100% new features for the next sprint.

4. Embedded Security Engineers

For high-risk or core platform teams, a Champion might not be enough.

- The Model: – A professional Security Engineer is fully “embedded” into the squad for a period (e.g., 3-6 months) or permanently.

- Role: – They write code alongside the developers, specifically focusing on security features (encryption, identity management, auditing).

- Benefit: – They provide deep expertise immediately, without the delay of waiting for an external review.

The Security Champions Program

This program identifies, trains, and empowers developers within each squad to act as the “security conscience” of their team. It is the most effective way to scale security culture without hiring an army of new staff.

1. Who is a Security Champion?

A Security Champion is not a full-time security engineer. They are a developer, QA engineer, or DevOps engineer who is already embedded in a product team.

2. Core Roles and Responsibilities

The Champion does not replace the security team; they extend it. Their job is to handle the “day-to-day” security tasks so the central team can focus on complex issues.

- The Voice of Security

- Standups: – They ensure security is mentioned in daily standups and sprint planning.

- Advocacy: – When a Product Owner pushes for a feature that skips security checks, the Champion is the first line of defense to say, “We need to secure this first.”

- Practical Execution

- Threat Modeling: – They lead simple threat modeling sessions (e.g., “What if an attacker tries to bypass this login?”) during the design phase.

- Code Review Assistant: – They act as a specialized reviewer for security-sensitive Pull Requests (PRs).

- Tool Triage: – When the automated scanner (SAST) reports 50 bugs, the Champion reviews them to decide which are real and which are false alarms.

3. Training and Cadence

A Champions program will fail if you just give them a badge and walk away. You must provide continuous value and community.

The “Belt” System – Training Levels

Gamify the training to encourage growth (similar to Martial Arts or Six Sigma):

- White Belt (Beginner): – Has completed basic security awareness training.

- Green Belt (Intermediate): Can run a basic SAST scan and explain the OWASP Top 10 to their team.

- Black Belt (Advanced): Can lead a Threat Modeling session and mentor new champions.

The Monthly Cadence

- Monthly Guild Meetings: – 1-hour session where all Champions gather.

- Agenda: 20 mins on a new attack technique, 20 mins on a tool demo, 20 mins of open Q and A.

- Office Hours: – The central security team holds open hours where Champions can drop in to ask questions without judgement.

- Slack/Teams Channel: – A private group for Champions to share news.

4. How to Launch the Program

- Recruitment

- Do not force it. Volunteers are 10x better than conscripts.

- Pitch the benefit “You will learn valuable skills that make you a better developer and increase your market value.”

- Enablement – give them the tools they need immediately.

- The Checklist: A simple 1-page PDF: “5 Things to Check Before Every Release.”

- Access: Give them elevated access to security dashboards (e.g., SonarQube, Snyk, DefectDojo).

- Reward and Recognition – being a Champion is extra work. You must reward it.

- Swag – Exclusive hoodies, stickers, or mugs that only Champions get.

- Career Growth: Work with their managers to ensure “Security Champion duties” are counted positively in their annual performance review.