6. Docker Networking: The Connectivity Matrix

Docker Networking is a virtual wiring system that defines how containers talk to each other, the host machine, and the outside world.

An Apartment Intercom System.

In a large building, you need different ways to communicate. Docker provides four main “plans”:

- None (Isolation Room): You are in a soundproof room with no phones. You are 100% safe, but you can’t talk to anyone.

- Bridge (Private Intercom): You have an internal phone. You can call other rooms in your apartment easily, but to call the outside world, you go through the building’s main switchboard.

- Host (Open Porch): You are sitting right on the street. Anyone passing by can hear you. It’s fast, but you have no privacy.

- Overlay (VPN Tunnel): A private line connecting your apartment in Delhi to your friend’s apartment in Bangalore. It feels like they are in the next room.

Docker handles the “cables and switches” of your virtual world automatically. As a beginner, you mostly need to know three things:

- Isolation by Default: Containers are born into a “Bridge” network. They are hidden from the internet unless you explicitly “open a window” using Port Mapping (e.g.,

-p 8080:80). - Naming Matters: In a “User-Defined” network, you don’t need to know a container’s ID number (IP). You just call it by its name, like

databaseorapi. Docker acts like a digital operator connecting your call. - Security Gates: You can put containers in different “rooms” (networks). A web server in the “Public Room” cannot talk to a database in the “Secret Room” unless you specifically build a door between them.

Key Tools:

- Docker CLI: Use

docker network lsto see your current “wiring.” - IPTable Guide: To understand how Docker actually moves data behind the scenes.

—

6.1. Bridge Network: The Standard Isolation

An Apartment Intercom System. – Imagine a large apartment building:

- The Bridge: This is the internal intercom. Every room (container) has a phone.

- Default Bridge: It’s like an old building. You must dial the room’s extension number (IP Address) to talk. If someone moves rooms, you lose them because their number changed.

- User-Defined Bridge: It’s like a modern smart building. You just press a button labeled “Security” or “Kitchen” (DNS Name). The system connects you automatically, no matter which room they are in.

When you install Docker, it automatically creates a virtual switch called docker0. Think of this as a “Virtual Power Strip” for networking.

- Private Identity: Each container gets its own private IP address (usually starting with

172.x.x.x). This address is only visible inside your server. - Talking to the Internet (NAT): When a container wants to download an update from internet, Docker acts as a translator (Network Address Translation). It sends the request using your server’s real IP, receives the answer, and passes it back to the container.

- Why “User-Defined” is better:

- Automatic DNS: You can call containers by name.

- Isolation: Containers on “Bridge A” cannot talk to containers on “Bridge B.” This is like having separate floors in a building that can’t see each other.

- Docker Engine: The core software that creates these bridges.

—

DevSecOps Architect

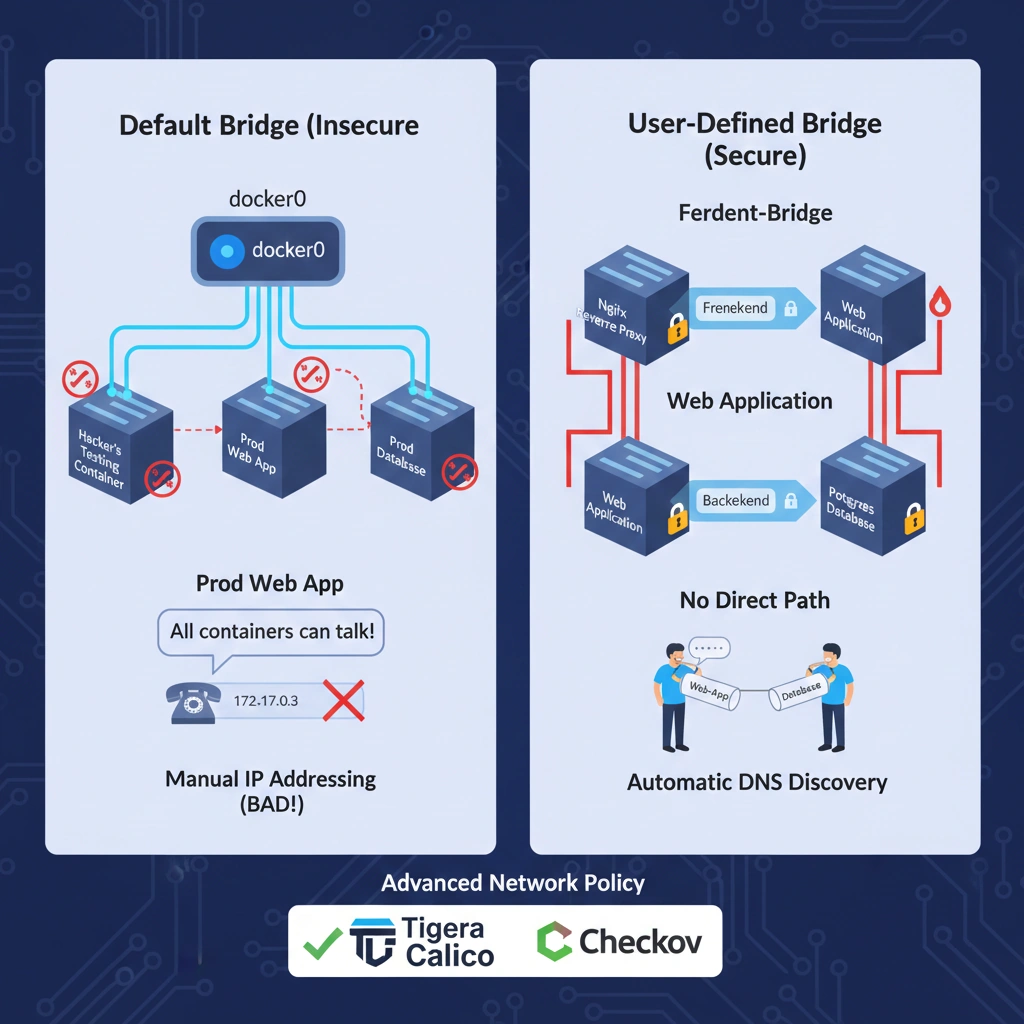

As an architect, you must never rely on the default bridge for production. You use Custom Bridge Networks to enforce the Principle of Least Privilege.

The Default Bridge Risk – On the default bridge, all containers can talk to each other by default (Inter-Container Communication). If a hacker compromises a simple “Testing” container, they can potentially “sniff” traffic from your “Production” container on the same default bridge.

The “Multi-Bridge” Isolation Strategy – A secure architecture uses multiple bridges to create a DMZ (Demilitarized Zone):

- Frontend-Bridge: Connects the Reverse Proxy (Nginx) and the Web App.

- Backend-Bridge: Connects the Web App and the Database.

- Result: The Database has zero network path to the Reverse Proxy. Even if the Proxy is hacked, the Database remains invisible.

- Tigera Calico: For advanced network policy enforcement (locking down which ports can talk to which containers).

- Checkov: To scan your Docker Compose files to ensure you aren’t using the insecure default bridge.

—

—

Technical challenges

| Challenge | Impact | Architect’s Solution |

| IP Overlap | Docker’s default IP range might conflict with your Office VPN. | Manually define the subnet and gateway when creating a user-defined bridge. |

| DNS Resolution Failure | Containers can’t find each other by name. | Ensure you are using a User-Defined Bridge; the default bridge does not support DNS. |

| Performance Overhead | NAT translation adds a few milliseconds of latency. | For high-speed trading or database-heavy apps, consider using the host network (with extreme caution). |

—

Practical Lab: Building a User-Defined Bridge

1 Create your own private network:

docker network create my-secure-net2 Launch a Database on this network:

docker run -d --name db-server --network my-secure-net alpine sleep 10003 Launch an App and “Call” the DB by name:

docker run -it --network my-secure-net alpine ping db-serverNotice how it works immediately without you providing any IP address!

—

Cheat Sheet

| Feature | Default Bridge | User-Defined Bridge |

| DNS Resolution | No (IP only) | Yes (Name-based) |

| Isolation | Shared by all | Private/Segmented |

| Configuration | Static | Flexible/Hot-pluggable |

| Production Ready | No | Yes |

6.2. Host Network: No Isolation

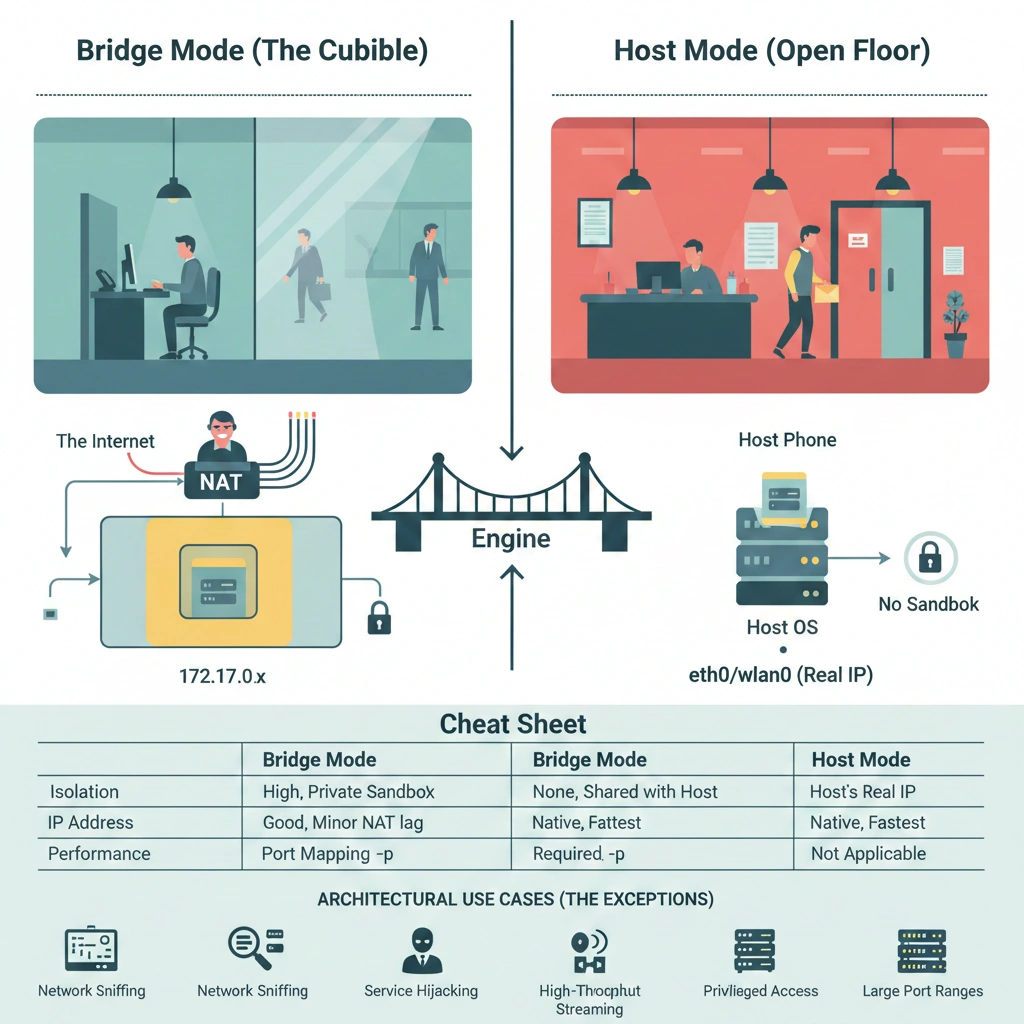

Think as: An Open Porch vs. a Private Room.

- Bridge (The Cubicle): You have your own desk and your own phone line. If you want to talk to the world, you go through the company switchboard (NAT). You are safe and private.

- Host (The Open Floor): You are sitting right at the front desk. You use the main building’s phone and front door. It’s much faster to get mail and talk to visitors, but everyone walking past can see exactly what you are doing.

Normally, Docker creates a “sandbox” (a protected play area) for your app. The Host network mode throws that sandbox away for networking purposes.

- No Private IP: The container doesn’t get a hidden address like

172.17.0.x. It simply uses the real IP address of the server. - No Port Mapping: Usually, you have to tell Docker to “link” ports (like

-p 8080:80). In Host mode, if the app inside the container uses Port 80, it is immediately live on your server’s Port 80. - Maximum Speed: Because the data doesn’t have to travel through a “virtual switch” (the Bridge), it moves at the fastest speed your hardware allows. There is no “middleman” slowing things down.

- Docker Engine: The core tool that manages these network modes.

—

DevSecOps Architect

As an architect, you must treat --network host as a high-risk exception, not a standard. By using this mode, you are bypassing the Linux Network Namespace isolation.

The Security “Nightmare” Explained

In a standard Bridge network, a container is restricted. In Host mode:

- Network Sniffing: A compromised container can use tools like

tcpdumpto listen to all traffic passing through the physical network card (eth0), including traffic intended for other containers. - Service Hijacking: The container can attempt to bind to local services (like a local database or SSH) that were intended to be “host-only.”

- Privileged Access: Host networking often requires the container to run with increased privileges, making a “Container Escape” much easier for a hacker.

Architectural Use Cases (The Exceptions)

Architects only approve Host networking for:

- System Monitoring: Tools like Prometheus Node Exporter that need to see real hardware metrics.

- High-Throughput Streaming: Media servers or VoIP apps where every microsecond of NAT latency causes lag.

- Large Port Ranges: If an app needs thousands of ports open (like some SIP/VoIP servers), mapping them one by one in a bridge is impossible.

- CIS Docker Benchmark: Use this to audit if host networking is being misused in your environment.

—

Use Case: Real-Time Network Monitoring

You need to monitor the health of your physical server. You deploy a Netdata or Prometheus container. If you put it in a Bridge, it only sees the “false” virtual network. By using --network host, the container can “see” the actual physical network traffic, helps to debug.

—

—

Technical Challenges

| Challenge | Impact | Architect’s Fix |

| Port Conflicts | Two containers cannot both use Port 80 on the same host. | Use Bridge networks or assign containers to different physical servers. |

| No Port Mapping | The -p flag is ignored; you can’t change ports at runtime. | You must change the port configuration inside the application code/config. |

| Security Exposure | High risk of the container attacking the Host OS. | Use AppArmor or SELinux profiles to restrict the container’s actions. |

—

—

Practical Lab: “The Unprotected App”

- Run a container in Host mode:

docker run -d --name host-web --network host nginx:alpine - Check your Ports (without mapping!):

netstat -tulpn | grep 80#You will see Nginx listening directly on your host’s Port 80! - Check the IP:

docker exec host-web ip addr#You will see your physical server’s IP (eth0/wlan0), not a private 172.x.x.x IP.

—

Cheat Sheet

| Feature | Bridge Mode | Host Mode |

| Isolation | High (Private Sandbox) | None (Shared with Host) |

| IP Address | Private (172.x.x.x) | Host’s Real IP |

| Performance | Good (Minor NAT lag) | Native (Fastest) |

| Port Mapping | Required (-p) | Not Applicable |

6.3. Overlay Network: The Multi-Host Machine Network

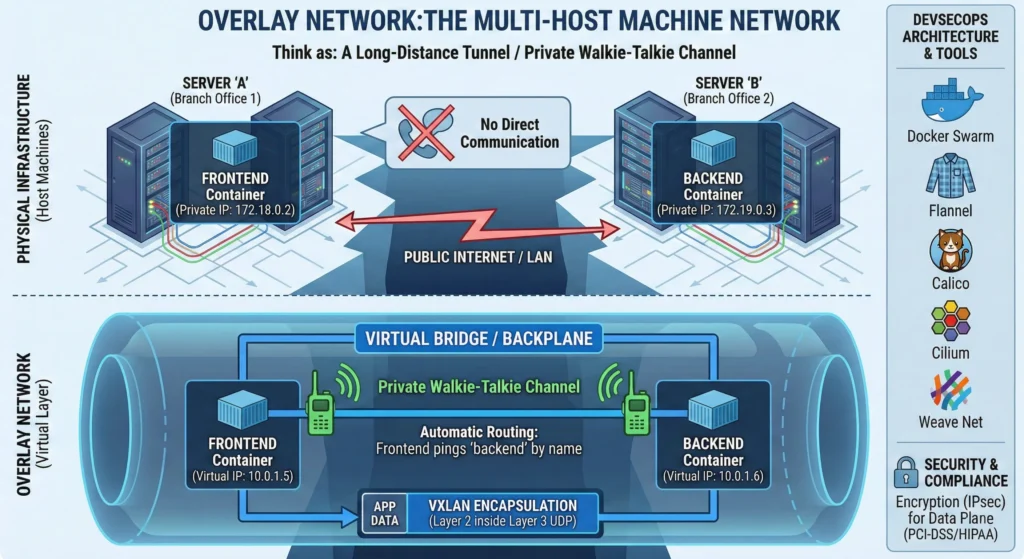

The Overlay Network, the technology that allows containers across different physical machines to talk to each other as if they were side-by-side.

Think of an Overlay network as a “Long-Distance Tunnel.” Usually, containers on different servers can’t see each other easily. An Overlay network creates a virtual bridge over the physical servers, allowing containers to communicate privately across a cluster.

Think as: A private walkie-talkie channel used by employees in two different branch offices. Even though the offices are in different cities, they can talk to each other instantly on the same channel without dialing long-distance phone numbers.

When your gets more app count for one server node, you add more servers. But how do containers on Server “A” talk to containers on Server “B“? The Overlay network handles this.

- Virtual Layer: It creates a “Virtual” network that sits on top of your physical internet/LAN.

- Automatic Routing: You don’t need to worry about the IP address of the physical server; Docker or Kubernetes finds the right “house” for your data.

- Privacy: Traffic stays inside this virtual bubble, hidden from the outside world.

- Docker Swarm: Uses built-in Overlay drivers.

- Flannel: A simple way to configure overlay networks for Kubernetes.

—

DevSecOps Architects Prospective

In a multi-host environment, the Overlay network is the “Backplane.” It uses VXLAN (Virtual Extensible LAN) encapsulation to wrap Layer 2 Ethernet frames into Layer 3 UDP packets.

- Service Discovery: Overlay networks integrate with internal DNS. A “Frontend” container can ping “Backend” by name, regardless of which physical node they reside on.

- Control Plane vs. Data Plane: The “Control Plane” manages how nodes join the network (often encrypted by default), but the “Data Plane” (the actual app data) often requires manual encryption settings.

- Security (IPsec): For compliance (PCI-DSS/HIPAA), you must encrypt the data plane.

- Calico: High-performance networking and security policy provider.

- Cilium: eBPF-based networking with advanced security observability.

- Weave Net: Creates a resilient mesh network between hosts.

—

Use Case: Global Microservices

A bank runs its “Transaction Service” on AWS and its “Analytics Service” on an on-premises data center. By using an Overlay Network, these two services communicate securely as if they were in the same room, shielding sensitive financial data from the public internet.

—

—

Technical Challenges

| Challenge | Impact | Architect’s Solution |

| MTU Overhead | Encapsulation adds 50 bytes to packets, causing fragmentation. | Adjust Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU) settings to 1450 instead of 1500. |

| Performance Lag | Wrapping/unwrapping packets (VXLAN) adds CPU latency. | Use “Direct Routing” modes in CNI plugins or hardware-accelerated NICs. |

| IP Exhaustion | Large clusters can run out of internal IP addresses. | Design larger subnets (e.g., /16) at the start of the cluster lifecycle. |

—

Cheat Sheet

| Feature | Bridge Network | Overlay Network | Host Network |

| Scope | Single Host | Multi-Host (Cluster) | Single Host |

| Best For | Standalone containers | Swarm / Kubernetes | High-performance / System tools |

| Isolation | High | High (Virtual) | None (Shared with OS) |

| Performance | Standard | Medium (Encapsulation) | Maximum (Fastest) |

6.4. Macvlan & IPvlan

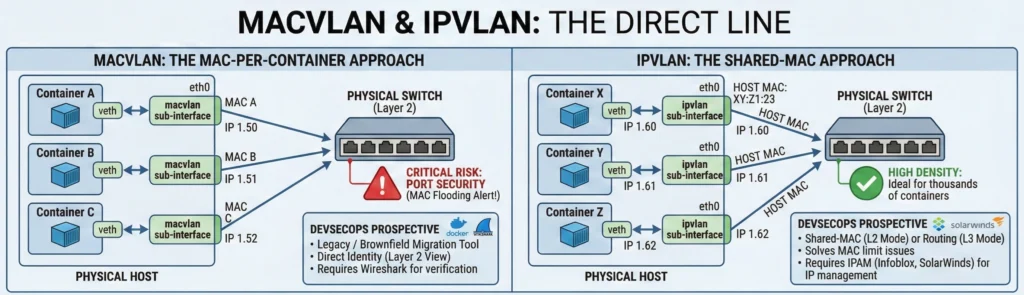

The “Direct Line” Normally, Docker containers are “hidden” behind your server (using the Host’s IP). Macvlan and IPvlan give containers their own direct identity on your physical network, making them visible to your router as if they were separate servers plugged into the network.

Think as:

- Bridge (Standard): Like an employee using a company extension. All calls go through the main switchboard.

- Macvlan (Real Desk): Like an employee getting their own dedicated phone line and desk. The mailman (Router) delivers mail directly to them.

- IPvlan (Shared Desk): Like two employees sharing the same phone line but having different names. It saves space (MAC addresses) but looks like one location to the office manager.

Usually, Docker acts like a “middleman” (NAT) for your containers. While this is secure, some old or specific software doesn’t like it.

- Direct Identity: Macvlan gives each container its own unique hardware ID (MAC address). Your home or office router sees a “new device.”

- No Translation: Data doesn’t have to be “translated” by the host server, which makes communication slightly faster.

- Bypassing the Host: This is often used for “Legacy” apps software built 10-15 years ago that expects to be the only thing running on a physical server.

- Docker Engine: Built-in support for both drivers.

- Wireshark: Used to verify if containers are appearing correctly with their own MAC/IP on the wire.

—

DevSecOps Architects Prospective

Architects should treat these as “Migration Tools” rather than “Modern Cloud Tools.” They are essential for moving “Brownfield” (old) applications into Docker.

- Macvlan (The MAC-per-Container approach)

- Logic: Every container gets a sub-interface and a unique MAC.

- Network View: It appears as a Layer 2 (Ethernet) device.

- Critical Risk: Port Security. Most enterprise switches (Cisco/Juniper) limit the number of MAC addresses per port. If you spin up 50 containers, the switch might trigger a “MAC Flooding” alert and kill your server’s connection.

- IPvlan (The Shared-MAC approach)

- Logic: All containers share the Host’s MAC address but have unique IPs.

- L2 vs L3 Mode: IPvlan L2 acts like a switch; IPvlan L3 acts like a router (better for complex subnets).

- High Density: Ideal for thousands of containers where you don’t want to overwhelm the physical switch.

- Infoblox: For managing the IP addresses assigned to these containers so they don’t clash with office laptops.

- SolarWinds IPAM: To track “rogue” container IPs on the physical network.

—

Use Case: Legacy Telecom App

A company has a 10-year-old VoIP (Voice over IP) application. The app’s license is tied to a specific MAC address, and it refuses to run if it detects it is behind a NAT/Bridge. By using Macvlan, the DevSecOps team “tricks” the app into thinking it is on its own physical server, allowing them to modernize the infrastructure without rewriting the old code.

—

—

Technical Challenges

| Challenge | Impact | Architect’s Strategic Solution |

| Switch Port Security | Physical switch shuts down the port due to “MAC Flooding.” | Use IPvlan (shares 1 MAC) or request a “sticky MAC” limit increase from the NetOps team. |

| Cloud Incompatibility | AWS/Azure/GCP block “Promiscuous Mode” needed for Macvlan. | Avoid Macvlan in Public Clouds; use the cloud provider’s native CNI (like AWS VPC CNI). |

| Host-to-Container Silence | By default, the Host cannot ping its own Macvlan containers. | Create a separate Macvlan Bridge on the host to act as a communication “loopback.” |

—

Practical Lab: Bypassing the Bridge

- Identify your Network Interface:ip addr show (Let’s assume it’s eth0).

- Create a Macvlan Network:docker network create -d macvlan –subnet=192.168.1.0/24 –gateway=192.168.1.1 -o parent=eth0 mv_net

- Run a Container with a Fixed IP:docker run -d –name legacy-app –network mv_net –ip 192.168.1.50 nginx

- Verification:Pinging 192.168.1.50 from another physical laptop on the same Wi-Fi/LAN will work, even if it doesn’t know Docker exists!

—

Cheat Sheet

| Feature | Macvlan | IPvlan (L2) | IPvlan (L3) |

| MAC Address | Unique for every container | Shared with Host | Shared with Host |

| Switch Impact | High (MAC per container) | Low (1 MAC total) | Low (1 MAC total) |

| Complexity | High (Network config) | Medium | High (Routing config) |

| Best For | Legacy apps / SNMP / IDS | High-density containers | Routing across subnets |

6.5. Architect’s Networking Comparison Table

| Network Driver | Performance | Security Isolation | Best For | DevSecOps Guru Tool Link |

| Bridge | Moderate | High | Default for microservices on a single host. | Docker Bridge Guide |

| Host | Native | None | System monitoring, high-speed networking tools. | Host Network Security |

| Overlay | Moderate | High | Multi-host clusters (Swarm/Kubernetes). | Docker Overlay Guide |

| None | N/A | Maximum | Network-isolated batch jobs or secret processing. | Docker Network Drivers |

| Macvlan | High | Medium | Legacy apps needing direct physical IPs. | Macvlan Documentation |

| IPvlan | High | Medium | High-density containers sharing one MAC. | IPvlan Documentation |

Think of Docker Networking like a Building’s Security System. Bridge is like having a private intercom for your office. Host is like taking the front door off its hinges anyone can walk in. Overlay is like a secure VPN tunnel connecting two different office branches. As an Architect, your job is to build the smallest, most restricted “intercom” possible for each service.