1. The Compute Evolution Physical vs. Virtual vs. Containerization

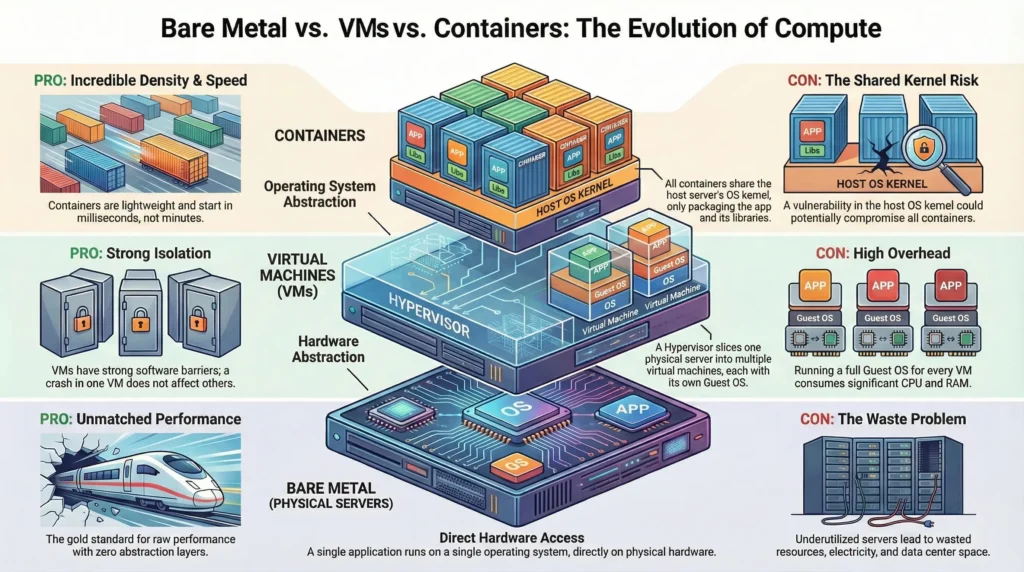

Compute evolution is the journey from buying a whole building for one office (Physical) to dividing a building into apartments (Virtual) to simply booking a flexible hotel room (Containers).

As an architect, choosing where your application runs are the first critical decision. It dictates your performance ceiling, your security posture, your costs, and how fast you can scale.

1.1 Physical Servers: Bare Metal

You buy a standalone bungalow. You own the land, the plumbing, and the roof. It’s private and powerful, but expensive to maintain.

“One hardware, one OS.”

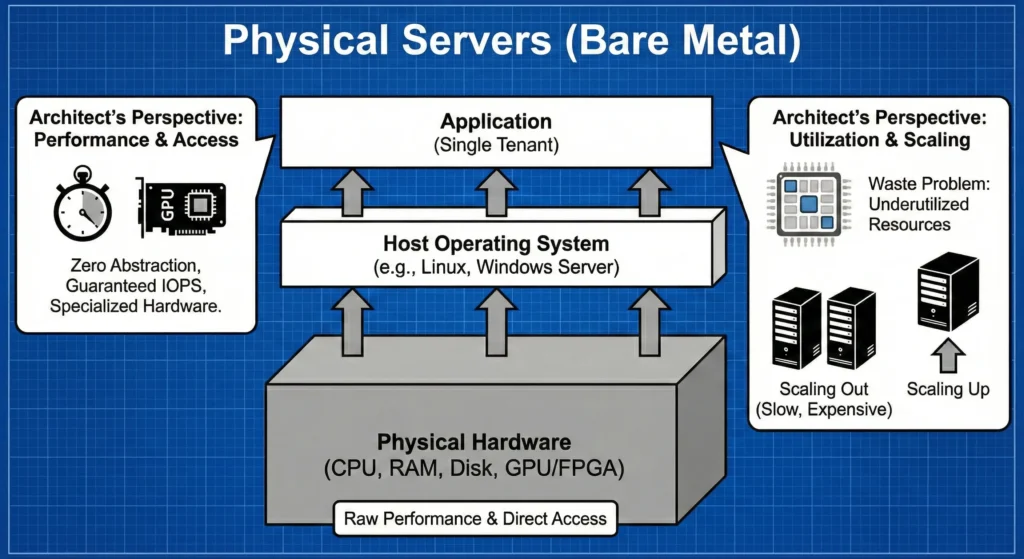

A physical server, often called “Bare Metal,” is the traditional approach. You buy a physical machine, install a single Operating System (OS) on it, and run your applications directly on that OS.

The Architecture – a direct, one-to-one stack. The application talks directly to the OS, and the OS talks directly to the hardware.

DevSecOps Architect prospective

As an Architect, you choose Bare Metal when “good enough” performance isn’t enough. You need the Absolute Ceiling of the hardware.

- Zero Abstraction Overhead: In VMs, there is a “Hypervisor” layer that steals a bit of CPU power. In Docker, there is a “Container Engine.” In Bare Metal, there is nothing between the app and the hardware. This is critical for High-Frequency Trading (HFT) or Massive Databases (Oracle/SAP).

- Direct Hardware Access: If you are doing AI/ML training, you need the OS to talk directly to the NVIDIA GPU drivers without any virtual layers slowing things down.

- The “Noisy Neighbor” Solution: In shared environments (Cloud), another user’s heavy traffic can slow your app down. On Bare Metal, you are the only “neighbor.” Your IOPS (Input/Output per second) are guaranteed.

From a DevSecOps view, Bare Metal offers the Physical Air-Gap.

- Hardened Isolation: There is no risk of “VM Escape” or “Container Breakout” where a hacker jumps from one user’s environment to another.

- Root of Trust: You can use hardware-level security like TPM (Trusted Platform Module) to ensure that the OS booting up hasn’t been tampered with by hackers.

- Compliance: Some government or banking regulations strictly forbid sharing hardware with other companies. Bare Metal is the only way to meet these “Single-Tenant” requirements.

Technical challenges

| Challenge | Impact | Architect’s Reality |

| Underutilization | The ROI Trap. | Most bare-metal servers run at only 15-20% CPU capacity. You pay 100% of the cost for 20% of the work. |

| Configuration Drift | Snowflake Servers. | Since these live for years, engineers manually change settings. Eventually, no one knows exactly how it was set up. |

| Disaster Recovery | High RTO (Recovery Time). | If the motherboard dies, you must find exact matching hardware to restore backups. This can take days, not minutes. |

| Operational Toil | Manual Labor. | You must worry about physical things: dust in the fans, failing power supplies, and data center cooling. |

—

Use Case: High-Performance Fintech

Scenario: A stock trading platform where 1 millisecond of delay (latency) equals millions of dollars in lost profit.

- The Choice: Bare Metal.

- The Setup: A Linux OS tuned specifically for the CPU architecture.

- The Result: Because there is no virtualization layer (Hypervisor) “interrupting” the CPU to handle other tasks, the trading app gets 100% of the processing power exactly when it needs it.

—

1.2. Virtual Machines: VMs

You live in an apartment building. You have your own kitchen and bathroom (Guest OS), but you share the land and foundation.

The Consolidation Era: “Hardware Abstraction.”

If a Physical Server is a standalone house, a Virtual Machine is an Apartment Building.

- The Hardware is the land.

- The Hypervisor is the building manager who divides the land into separate units.

- The VM is your individual apartment.

Inside your apartment, you have your own front door, your own kitchen, and your own bathroom (this is the Guest OS). You don’t see what your neighbors are doing. If your neighbor’s kitchen catches fire (a Kernel Panic), your apartment is safe because of the thick firewalls (The Hypervisor).

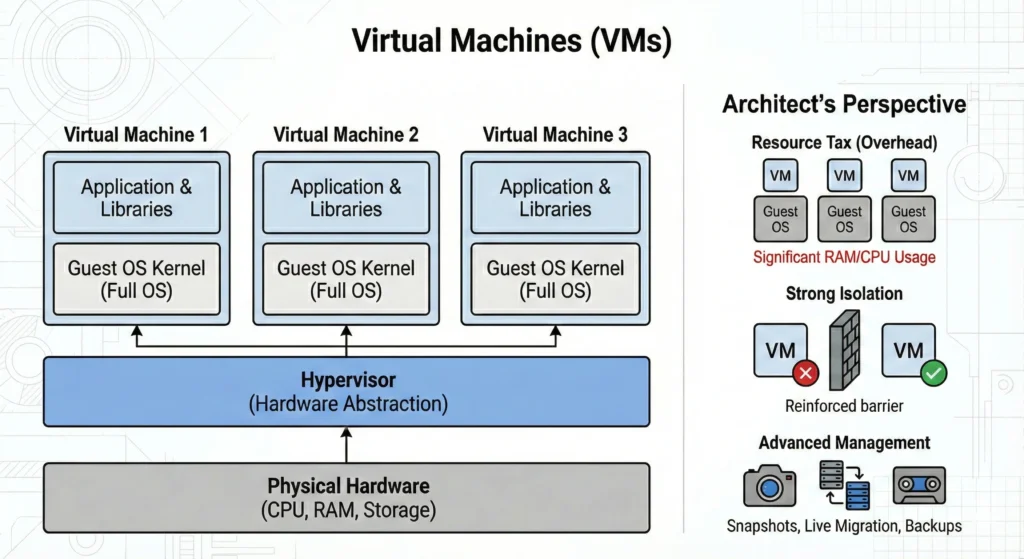

Virtualization changed everything by introducing the Hypervisor. A Hypervisor is software that sits on top of physical hardware and lies to operating systems. It tricks multiple “Guest” operating systems into thinking they have their own dedicated hardware.

The Architecture – The Hypervisor slices the physical CPU, RAM, and storage into virtual chunks. Each VM gets a full, complete Guest OS.

DevSecOps Architect perspective

The magic comes at a cost. Every VM runs a full Guest OS kernel. Running 10 VMs means running 10 separate Linux kernels, 10 separate package managers, and 10 separate sets of background services. This eats up significant RAM and CPU just to keep the VMs alive, before your app even runs.

- Isolation (Strong Software Barriers): The Hypervisor provides strong isolation. If VM A crashes due to a kernel panic, VM B is unaffected because they are running totally separate kernels. This is crucial for multi-tenant environments (like AWS EC2).

- The Hypervisor (Type 1 vs. Type 2):

- Hardware Emulation: The Hypervisor creates “Virtual Hardware.” The Guest OS thinks it has a real Intel CPU and a real Realtek Network Card, but these are just software definitions.

- Management: VMs introduced snapshots, live migrations (moving a running VM from one physical server to another), and easier backups.

- The Resource Tax: Because each VM is a “Full Computer,” it needs its own memory for its own kernel. If a Linux kernel takes 500MB of RAM, and you run 20 VMs, you have lost 10GB of RAM just to keep the “Guest OSes” alive before any application code even runs.

In the DevSecOps world, VMs provide Hardware-level Virtualization Isolation.

- Strong Boundaries: Since each VM has its own Kernel, a “Kernel Exploit” in VM “A” cannot easily affect VM “B”. The Hypervisor acts as a powerful security guard.

- Snapshot & Rollback: If a VM is hacked or a patch fails, an architect can “Snapshot“(Backup) the VM before the change. If things go wrong, it can be restored back.

- Live Migration (vMotion): If a physical server is failing, the Hypervisor can move a running VM to another physical server without the user even noticing a flicker.

Technical challenges

- The “Slow Boot” Problem: Because a VM has to initialize virtual hardware and “boot” a full OS kernel, it takes minutes to start. In a world of “Auto-scaling” during a flash sale, minutes are too slow.

- Storage Bloat: Each VM carries a 20GB+ virtual hard drive just for its OS files. If you have 100 VMs, that is 2 Terabytes of storage just for redundant OS files.

- Hyperjacking: This is a rare but “Level 10” security risk where a hacker compromises the Hypervisor itself. If they control the Hypervisor, they own every single VM on that physical server.

- Licensing Costs: Often, you have to pay for a license for every “Guest OS” instance, which makes scaling very expensive.

1.3. Containers

You stay in a hotel room. You share the plumbing and electricity (Kernel) with others, making it super fast to check in and out.

The Agility Revolution: “OS Abstraction.”

If a Physical Server is a standalone house and a VM is an apartment with its own kitchen and bathroom, then a Container is a Hotel Room.

- The Hardware is the hotel building.

- The Host OS Kernel is the hotel’s shared plumbing, electricity, and HVAC system.

- The Container is your room.

You have your own private space, your own bed, and your own key. But you don’t have a private kitchen or a private power generator; you use the building’s shared services. Because you don’t have to “build a kitchen” in every room, the hotel can have hundreds of rooms in the same space. Moving in is as fast as walking through the door you don’t wait for the electricity to be turned on because it’s already running for the whole building.

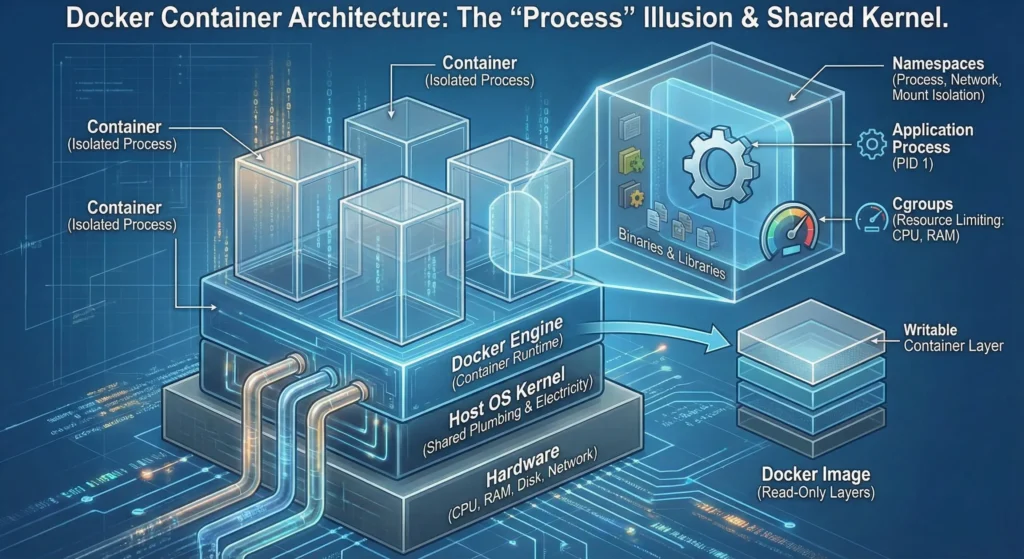

If VMs virtualize the hardware, containers virtualize the Operating System.

Containers get rid of the Hypervisor and the Guest OS entirely. They use features built directly into the Linux host kernel (Namespaces and Cgroups) to isolate processes.

The Architecture – All containers on a host share the same, single Host OS Kernel. The container itself only holds your application and its specific dependencies (binaries and libraries).

DevSecOps Architect perspective

As an architect, you choose containers to achieve immutability and massive scale.

- Density & Efficiency: Because you aren’t running separate Guest OS kernels, containers are incredibly lightweight. A VM might require 1GB of RAM just to boot; a container might need only 10MB. You can pack dozens of containers onto a host that could only support a few VMs.

- Speed: Containers don’t “boot.” They just start a process. Startup times are in milliseconds, not minutes. This is vital for auto-scaling in the cloud.

- Portability: Because the container packages all its dependencies, it runs exactly the same on a developer’s laptop as it does in production.

- The Security Trade-off (Shared Kernel Risk): This is the critical architectural constraint. Because all containers share the host kernel, if a hacker finds a vulnerability in the Linux kernel, they could potentially break out of the container and compromise the entire host. Stronger security measures (like Seccomp, AppArmor, and User Namespaces) are required in production.

- The “Process” Illusion: A container is essentially just a Linux Process with a “Virtual Reality headset” on. It thinks it is a full computer because the Kernel hides everything else from it.