2. Docker Internals

Building Secure, Scalable, and Production-Ready Container Ecosystems.

Docker Internals is the “Magic Trick” that uses Linux Kernel features to make a normal process feel like it’s running on its own private computer.

Think of Virtual Reality (VR) Cubicle Imagine you are in a massive warehouse. You put on a VR Headset (Namespaces). Suddenly, you only see your desk and your files; the other 100 people in the warehouse disappear. The building manager gives you a Resource Budget (Cgroups) you can only use 2 liters of water and 1 hour of electricity. If you try to use more, the power cuts off. You feel like you are in a private office, but you are actually just one person in a shared warehouse.

- The Warehouse (Host OS): Provides the roof, electricity, and plumbing (The Kernel).

- The Cubicle Walls (Namespaces): You can only see what is inside your desk. You don’t know who is in the next cubicle.

- The Company Policy (Cgroups): You are only allowed to use 2 sheets of paper and 1 pen (Resource Limits). If you try to take more, the manager stops you.

- The Security Guard (DevSecOps): Ensures no one tries to climb over the walls to steal files from the warehouse manager’s office.

Most people know how to run a container; very few know how to architect a secure container supply chain. By this notes, you won’t just be “using” Docker you will be designing high-availability systems, securing images against hackers, and automating multi-arch builds for global scale.

Don’t just run it; understand how it breathes.

- What is a Container? It’s NOT a Mini-VM. It’s just a process with a “fencing” around it.

- Namespaces: The “Wall.” It isolates what the process can see “Network, Users, Files“.

- Cgroups (Control Groups): The “Quota.” It limits how much RAM/CPU a container can eat so it doesn’t crash your whole server.

- The Ecosystem: Understanding the relationship between Docker Engine, containerd, and runc.

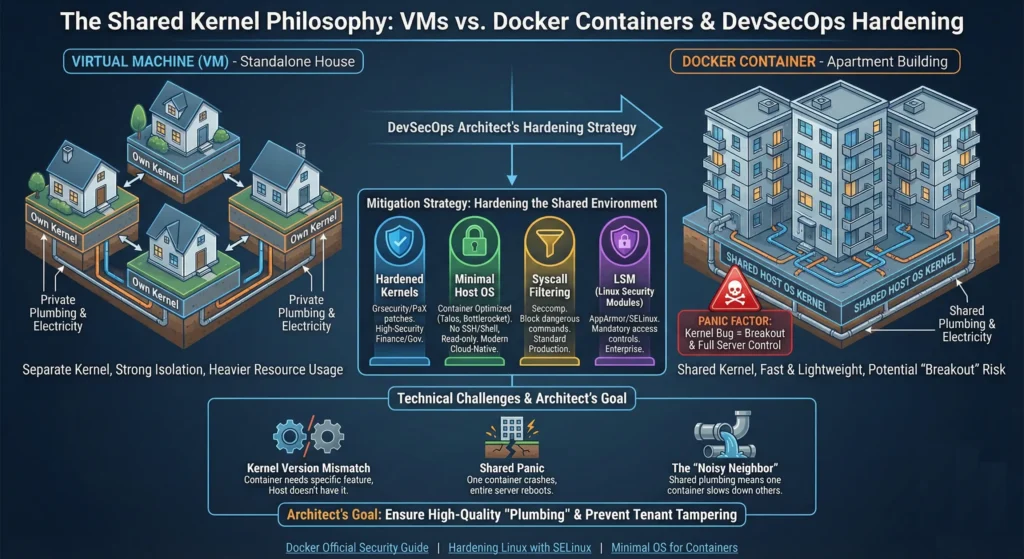

2.1. The Shared Kernel Philosophy

In a Virtual Machine, every VM has its own Kernel. In Docker, every container on a host shares the same Host OS Kernel.

- Because the kernel is shared, containers are incredibly fast and lightweight (starting in milliseconds).

- “Panic” Factor: If a hacker finds a bug in the Linux Kernel, they can “break out” of the container and control the entire physical server. so always use a Hardened Kernel (like Hardened Linux).

As a DevSecOps Architect, you don’t stop using Docker because of these risks; you harden the environment.

| Mitigation Strategy | How it works | Architect’s Choice |

| Hardened Kernels | Using kernel patches like Grsecurity or PaX that make it much harder for exploits to work. | High-Security Finance/Gov |

| Minimal Host OS | Using a “Container Optimized” OS like Talos, Bottlerocket, or CBL-Mariner. These have no SSH, no Shell, and a read-only filesystem. | Modern Cloud-Native |

| Syscall Filtering | Using Seccomp (Secure Computing) to block dangerous commands (like mount or reboot) at the kernel level. | Standard Production |

| LSM (Linux Security Modules) | Using AppArmor or SELinux to create mandatory access controls for what a process can do. | Enterprise Enterprise |

Technical challenges

- Kernel Version Mismatch: Since containers share the host kernel, you cannot run a container that requires a specific Kernel feature if the Host OS doesn’t have it.

- Shared Panic: If one container triggers a “Kernel Panic” (a total crash), the entire physical server reboots, taking down all other containers.

- The “Noisy Neighbor”: Because the “plumbing” (CPU, RAM, I/O) is shared, one container can slow down everyone else if not properly limited.

Think of a VM like a Standalone House it has its own plumbing, electricity, and walls. If one house floods, the neighbor is dry. Think of a Container like an Apartment in a Building everyone shares the same plumbing (The Kernel). If the main pipe bursts, every apartment gets flooded.

Architect’s Goal: Your job is to make sure the “plumbing” is high-quality and that no “tenant” (container) can mess with the main valves.

- Docker Official Security Guide: Docker Security & The Kernel

- Hardening Linux with SELinux: SELinux Documentation

- Minimal OS for Containers: Bottlerocket OS (AWS)

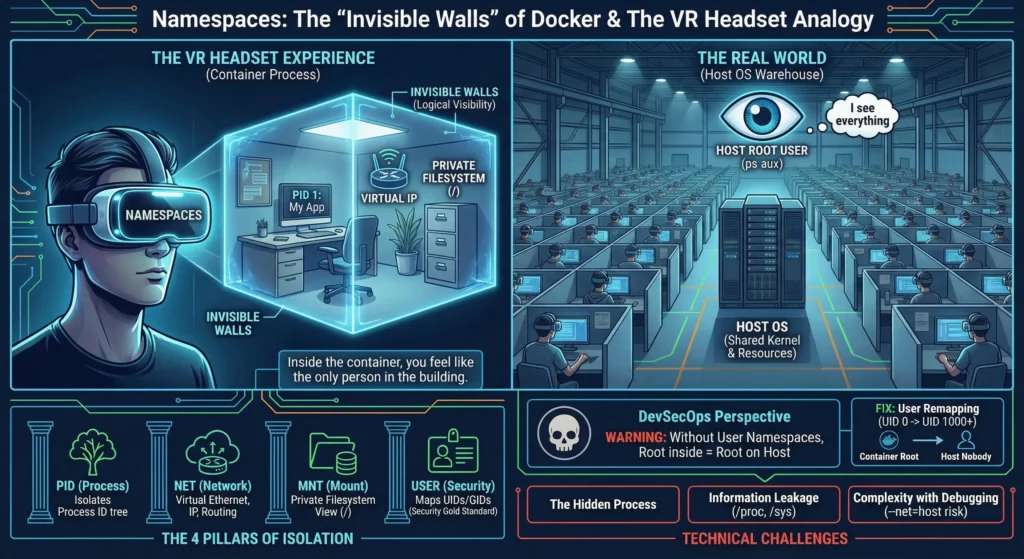

2.2. Namespaces: The “Invisible Walls”

Imagine you are wearing a Virtual Reality (VR) headset.

- When you put it on, you see a private office with your own computer, your own phone, and your own desk.

- You feel like you are the only person in the building.

- However, the “real world” is a giant warehouse where hundreds of other people are also wearing VR headsets.

Namespaces are the VR headset for a Linux process. They lie to the process, making it believe it has its own private network, its own files, and that it is the most important process (PID 1) in the system.

Namespaces are the magic that makes a process feel like it’s in a VM. Without Namespaces, Docker cannot exist.

Namespaces do not provide physical isolation; they provide logical visibility.

The 4 Pillars of Isolation

These four namespaces interact to create the “Container Sandbox.”

2.2.1. PID Namespace: Process Isolation

- In Linux, processes are organized in a tree. The first process started is PID 1 (usually

systemdorinit). It controls everything. - The Namespace Trick: When a container starts, the PID Namespace resets the counter. The container application inside thinks it is PID 1.

- Why it matters:

- Privacy: Process A cannot “see” Process B. You cannot run

killon a process you cannot see. - Stability: If the application (PID 1 inside the container) dies, the Namespace collapses, and the container stops.

- Privacy: Process A cannot “see” Process B. You cannot run

- DevSecOps Warning (The “Zombie” Risk): Standard Linux apps don’t expect to be PID 1. They don’t know how to handle “kill signals” or clean up dead child processes (Zombies). Fix: Use an init wrapper like

tini(docker run --init).

2.2.2. NET Namespace: Network Isolation

- By default, if two apps try to listen on Port 80, the second one fails.

- The Namespace Trick: The NET Namespace gives the container its own completely separate “Network Stack.”

- It gets its own eth0 (Virtual Ethernet).

- It gets its own Loopback (localhost).

- It gets its own IP Address.

- How they talk: Docker creates a “Bridge” (usually

docker0) on the host. It connects the container’s virtual cable (veth) to this bridge so it can reach the internet.

2.2.3. MNT Namespace: Filesystem Isolation

- This is the evolution of the old

chrootcommand. - The Namespace Trick: It changes what the process sees as the “Root” directory (

/).- When the container looks at

/bin, it sees the files provided by the Docker Image (e.g., Ubuntu or Alpine), NOT the files on the actual Host OS.

- When the container looks at

- This allows to run an app that needs

Python 2.7on a Host that only hasPython 3.10. The container doesn’t even know the Host’s Python exists.

2.2.4. USER Namespace: Identity Isolation

- The most critical (and often ignored) security layer.

- The Namespace Trick: It maps “User IDs” (UIDs) between the container and the host.

- Inside: The process looks like Root (UID 0). It can install packages and change configs.

- Outside: The Host Kernel sees that process as Nobody (UID 65534) or a standard user.

- Security Value: If a hacker breaks out of the container, they find themselves as a “Nobody” user on the host, with zero power to damage the system.

—

DevSecOps prospective

By default, Docker does not enable User Namespaces. This means if you are root inside the container, you are root on the host. If a hacker escapes the container, they own your entire server.

- Fix: Enable User Remapping. When enabled, Docker maps the container’s

root(UID 0) to a high-numbered UID on the host (like UID 1000).

—

Technical challenges

- The “Hidden” Process: While the container can’t see the host, the host can see everything inside the container. As a root user, if you run

ps auxon the host, you will see the container’s processes. This is why host security is still the 1st priority. - Information Leakage: Certain parts of the

/procand/sysfilesystems are not fully namespaced. A container might still be able to see how much total RAM the host has, which can lead to “Side-Channel Attacks.” - Complexity with Debugging: Sometimes, to fix a network issue, you have to “break the walls” by running a container with

--net=host. This is a massive security risk that architects should only allow in controlled environments.

—

- Linux Manual: Namespaces(7) – Overview of Linux Namespaces

- Docker Security: Isolate containers with a User Namespace

- Deep Dive: The 7 Namespaces of Linux

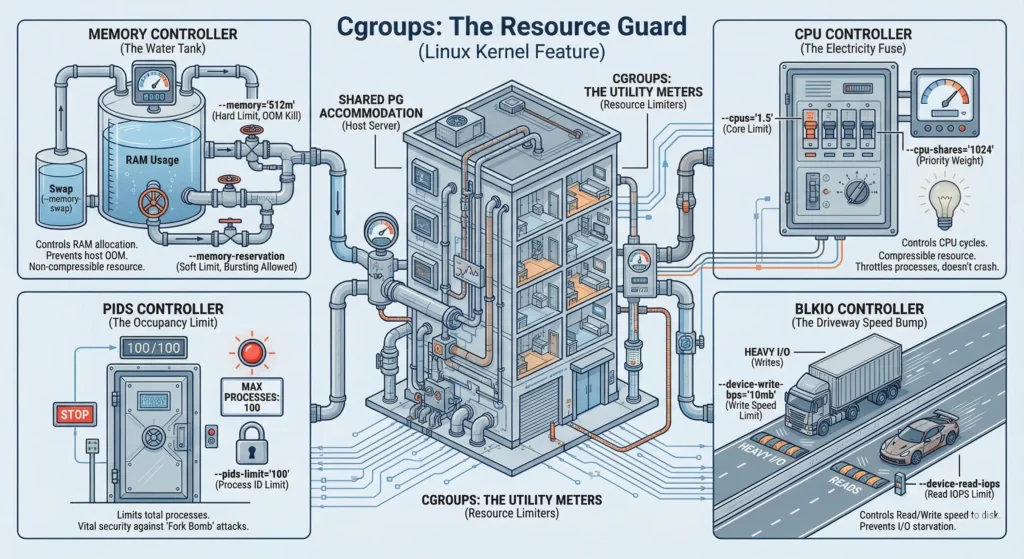

2.3. Cgroups: The Resource Guard

Imagine you are a landlord running a Shared PG (Paying Guest) Accommodation.

- Namespaces are the private rooms. You can’t see what other guests are doing.

- Cgroups are the Utility Meters. If one guest leaves the water tap open all day (Memory Leak) or uses all the Wi-Fi bandwidth for 4K streaming (CPU Usage), the other guests will suffer.

As the landlord (Architect), you install limiters:

- Water Meter: You can only use 50 liters a day (Memory Limit).

- Electricity Fuse: If you try to use too much power, only your fuse blows, not the whole building’s (OOM Killer protection).

- Internet Cap: You get high speed for 1 hour, then it slows down so others can work (CPU Shares).

Cgroups are a Linux Kernel feature that allows you to allocate resources such as CPU, system memory, network bandwidth, or combinations of these among hierarchically organized groups of processes.

—

2.3.1. The Mechanics: What can we actually limit?

As an architect, you must know the four main “subsystems” (controllers) that Docker uses:

These controllers are part of the Linux Kernel. Docker uses them to ensure one container doesn’t “eat” all the resources and crash the server.

2.3.1.1. Memory Controller (The Water Tank)

- Think you have a 500-liter water tank. If you try to use 501 liters, the pipe shuts off immediately.

- Controls the amount of RAM a container can use.

- Key Flags:

--memory="512m": Hard Limit. If the app hits this, the Kernel kills it (OOM Killed).--memory-swap: Limits how much “Swap” (Disk space acting as RAM) it can use.--memory-reservation: Soft Limit. Guarantees this amount but allows bursting if the server is free.

2.3.1.2. CPU Controller (The Electricity Fuse)

- Think you share the main power line. If you turn on too many ACs, the fuse doesn’t blow; instead, the power company just dims your lights (slows you down) so neighbors still get power.

- Controls CPU cycles. Unlike memory, CPU is “compressible” if you hit the limit, you just get slower, you don’t crash.

- Key Flags:

--cpus="1.5": You can use exactly 1.5 cores.--cpu-shares="1024": Priority weight. If the server is busy, a container with 1024 gets 2x the time as one with 512.

2.3.1.3. PIDs Controller (The Occupancy Limit)

- Think of fire safety rules say, “Maximum 10 people in this room.” If an 11th person tries to enter, the door won’t open.

- Limits the number of processes (Process IDs) inside a container. This is vital for security.

- Key Flags:

--pids-limit="100": The container can strictly run only 100 processes. If a hacker tries a “Fork Bomb” (a script that creates infinite viruses), it stops at 100 and fails.

2.3.1.4. BlkIO Controller (The Driveway Speed Bump)

- Think you are on the driveway and it is shared. If one person is moving furniture with a huge truck (Heavy Writes), they block everyone else. The security guard puts a speed bump to slow them down.

- Controls the Read/Write speed (I/O) to the hard disk.

- Key Flags:

--device-write-bps: Limit write speed (e.g., “10mb”).--device-read-iops: Limit how many “reads” per second (good for databases).

2.3.2. Cgroups v1 vs. Cgroups v2

For a long time, Cgroups were messy (v1). Modern Linux (Kernel 4.15+) introduced Cgroups v2, which is a unified hierarchy.

- Cgroups v2 is much more efficient and handles “Memory Pressure” better.

- Rootless Docker: You cannot run Docker in a fully secure “Rootless” mode (where even the daemon is unprivileged) effectively without Cgroups v2.

- Ensure your production nodes are running a modern OS (Ubuntu 22.04+ or RHEL 9) to leverage v2 features.

—

2.3.3. The “Noisy Neighbor” Problem

In a shared production environment, one container might have a Memory Leak. Without Cgroups, that one container will keep asking for RAM until the Host OS has none left.

- The Result: The Linux Kernel will start the OOM Killer (Out of Memory Killer).

- The Disaster: The OOM Killer might choose to kill your most important container (like your primary Database) just to save the system.

- Architect’s Mitigation:

- Hard Limits: Use

--memory="512m". If the app exceeds this, only that container is killed. - Reservations: Use

--memory-reservation="256m". This guarantees the container at least this much but allows it to burst if the host is idle.

- Hard Limits: Use

—

2.3.4. Architect’s Resource Checklist

| Feature | Docker Flag | Why Architects use it |

| Memory Limit | --memory | Prevents a single container from crashing the host. |

| Swap Limit | --memory-swap | Prevents the container from slowing down the host by using disk as RAM. |

| CPU Limit | --cpus | Ensures consistent application latency. |

| IO Limit | --device-write-bps | Prevents a log-heavy container from choking the Disk for everyone else. |

| PIDs Limit | --pids-limit | DevSecOps Priority: Stops Fork Bombs and process-exhaustion attacks. |

—

Technical challenges

- The OOM Killer Logic: When the host runs out of RAM, the Linux Kernel looks for a “victim” to kill. If you haven’t set limits, the kernel might kill your Database (which is using a lot of RAM) instead of the leaky script that caused the problem.

- Tip: Always set memory limits to ensure the kernel kills the “guilty” container, not the “valuable” one.

- Kernel Version Fragmentation: Moving a container from a Cgroup v1 host to a Cgroup v2 host can sometimes break monitoring tools that expect files in specific

/sys/fs/cgroup/paths. - The Swap Trap: If you limit RAM but not Swap (

--memory-swap), a leaky container will start using the hard drive as RAM. This won’t kill the container, but it will make the entire physical server crawl like a snail.

Cgroups provide Stability. A production container without Cgroup limits is a “Time Bomb.” By strictly defining RAM, CPU, and PID limits, you ensure that even if an application fails or is compromised, the rest of your infrastructure remains standing.

—

- Official Doc: Docker Resource Constraints

- Deep Dive: Kernel.org Cgroup v2 Manual

- Security: CIS Docker Benchmark (Section 4.5 – Resource Constraints)

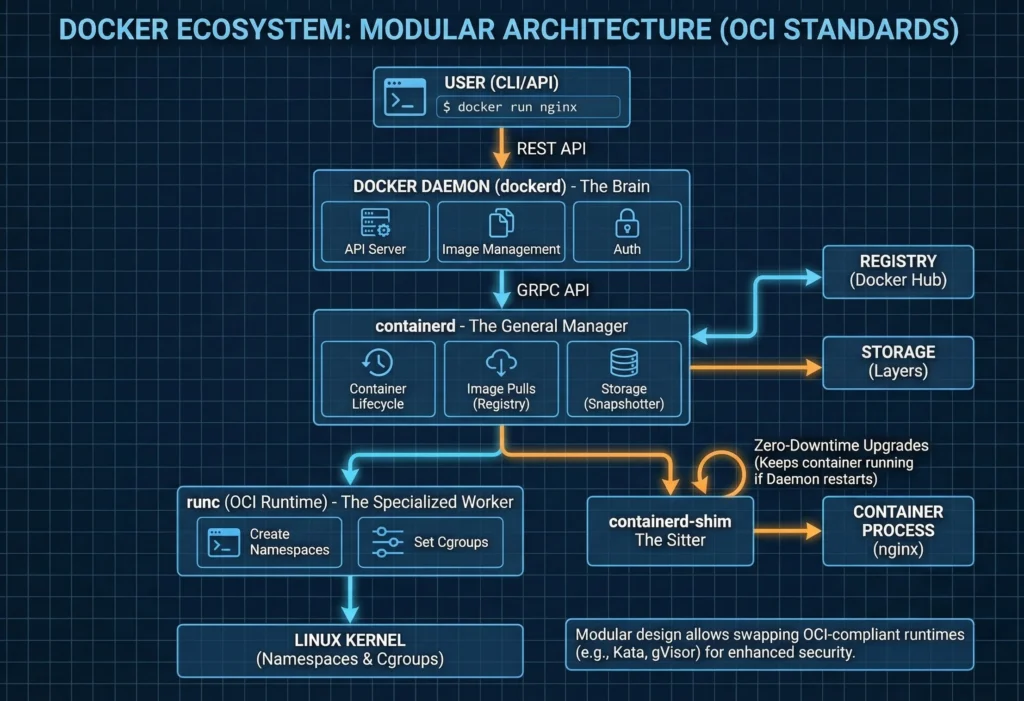

2.4. The Ecosystem: The Modular Architecture

Docker is not a single “binary.” It is a collection of tools working together.

Modern Docker follows the OCI (Open Container Initiative) standards. This modularity is what allows us to swap parts of the engine for more secure versions.

- Docker Daemon (dockerd): The brain. It handles the API requests, image management, and authentication.

- containerd: The “Manager.” It handles the high-level container lifecycle (pulling images, managing storage, and network attachment). It is so stable that Kubernetes uses it directly without Docker.

- runc: The “Worker.” It is a tiny tool that does only one thing: it talks to the Linux Kernel to create the Namespaces and Cgroups, starts the process, and then exits.

- containerd-shim: The “Sitter.” Every container has a shim process. This allows you to restart the Docker Daemon or

containerdwithout stopping your running containers. This is vital for Zero-Downtime upgrades.

Imagine you are running a high-end restaurant. You don’t just have one person doing everything; you have a Manager, a Head Chef, and Workers.

—

2.4.1. Docker Daemon (dockerd): The “Front Desk / Brain”

The Daemon is the “public face” of Docker. When you type a command like docker run, you are talking to the Daemon.

- It handles the Docker API. it checks if you are authorized to pull an image, manages your local images, and keeps track of networks and volumes.

- Simple Logic: It takes your high-level command and translates it for the “Manager” below it.

- Architect Note: If the Daemon hangs, you can’t send new commands, but thanks to the “Shim” (explained below), your already-running containers won’t die.

—

2.4.2. containerd: The “General Manager”

This is a very stable and powerful tool. It used to be part of Docker, but now it is an independent project used by Kubernetes as well.

- It manages the Container Lifecycle. It pulls the image from the registry (like Docker Hub), sets up the storage (the layers), and manages the network interface for the container.

containerdis designed to be “boring” and stable. It doesn’t care about your fancy CLI; it just cares about keeping containers alive and healthy. and Because it is smaller than the full Docker engine, it has a smaller “Attack Surface”.

—

2.4.3. runc: The “Specialized Worker”

runc is a tiny, lightweight tool that does only one job and then disappears.

- It is the tool that actually talks to the Linux Kernel. It creates the Namespaces (the walls) and Cgroups (the limits) we discussed earlier. Once the process is started and the container is “born,”

runcexits. - Simple Logic: It is the “Builder” who builds the house (container) and then leaves once the keys are handed over.

—

2.4.4. containerd-shim

This is the secret hero of Zero-Downtime infrastructure. Every single container has its own “Shim.”

- In the old days, if you restarted the Docker Daemon, all your containers would stop. This was a nightmare for production.

- The Shim sits between

containerdand the container. It keeps the “Input/Output” (logs) open and keeps the process running. - Because of the Shim, can upgrade Docker version or restart the Daemon, and the website stays Online. The container is “orphaned” for a second, but the Shim holds its hand until the Daemon comes back.

—

2.4.5. The Architecture Flow: What happens when you type docker run?

- You: Type

docker run nginx. - Docker CLI: Sends a “POST” request to the Docker Daemon.

- Docker Daemon: Validates your request, checks if you have the image, and tells containerd: “Hey, I need a container for Nginx.”

- containerd: Grabs the image, prepares the storage layers, and calls runc: “Please build the sandbox.”

- runc: Talks to the Linux Kernel, sets up Namespaces/Cgroups, and starts the Nginx process.

- containerd-shim: Becomes the “Sitter” for that Nginx process so it can stay alive independently.

- runc: Exits. Your container is now running.

2.5. DevSecOps Architect’s Hardening Checklist

| Feature | Risk if ignored | Architect’s Fix |

| Syscalls | Container makes a reboot or mount call to host. | Seccomp Profiles: Use the default Docker profile or a custom one to block dangerous system calls. |

| Linux Capabilities | Containers have powers like CHOWN or KILL by default. | Cap-Drop: Use --cap-drop=ALL and only add back what is needed (e.g., --cap-add=NET_BIND_SERVICE). |

| Filesystem Security | Hacker modifies the application code at runtime. | Read-Only Root: Use --read-only flag. This makes the entire container filesystem immutable. |

| The Socket | Mounting /var/run/docker.sock gives the container full control of the host. | Socket Protection: Never mount the Docker socket into a container unless it’s a trusted tool (like Portainer or Jenkins) and strictly guarded. |

—

Technical challenges

- The “Zombie” Problem – If a container’s main process (PID 1) finishes, but it has child processes left over, they can become “zombies” that eat up system resources.

- Fix: Use the

--initflag in Docker to include a tiny init-binary (liketini) that reaps these zombie processes.

- Fix: Use the

- The Socket Vulnerability – The Docker Daemon usually listens on a Unix socket (

/var/run/docker.sock).- Risk: If you mount this socket inside a container, that container can control the entire host. It can start new containers, delete images, or even shut down the server.

- Never mount the Docker socket in a public-facing container. If you need to manage Docker from a container, use a secure Proxy or the Docker API over TLS.

- Cap-Drop: Use

--cap-drop=ALLand only add back specific Linux capabilities likeNET_BIND_SERVICE. - Seccomp: Ensure the default Seccomp profile is active to block dangerous system calls (like

mount). - No-New-Privs: Use

--security-opt=no-new-privilegesto prevent processes from gaining more power than they started with.

2.6. Practical Lab for Architects: “Seeing the Matrix”

To truly understand internals, you must see them outside of Docker.

Task 1: The “Process” Reality Check

1: Run a container:

docker run -d --name secret_process alpine sleep 99992: On your host machine, run:

ps aux | grep sleepYou will see the sleep process running. It is NOT hidden inside some “black box.” It is a normal Linux process.

Task 2: Inspecting Cgroup Limits

1: Start a container with a limit:

docker run -d --name limited_app --memory="100m" alpine sleep 99992: Check the kernel’s limit file:

cat /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/docker/<container_id>/memory.limit_in_bytesDocker is just a “wrapper” that writes values into Linux configuration files.

Most people think Docker is a “Platform.” An Architect knows Docker is a standardized interface for Linux Kernel primitives. When you master Namespaces, Cgroups, and the modular runtime (containerd/runc), you gain the power to build systems that are not just portable, but technically bulletproof.

- Docker Internals: Docker Engine Architecture

- containerd Project: The containerd Handbook

- runc Specification: OCI Runtime Spec

- DevSecOps Hardening: CIS Docker Benchmark Guide

- Docker Security – Seccomp Guide