4. Registries and The Secure Supply Chain

A Docker Registry is a secure warehouse where your “Gold Images” are stored, versioned, and protected before they go to the production servers.

Imagine your code is vital medicine.

- Unverified Public Image (e.g.,

docker run mongo): This is like buying a random bottle of pills from a street vendor. It has a label, but you don’t know who made it, if it’s expired, or if it’s been tampered with. It might cure you, or it might poison you. - Your Secure Registry: This is a Verified Pharmacy. Every medicine bottle here has:

- A Batch Number (Version Tag): You know exactly when and how it was made.

- Tested for Purity (Vulnerability Scan): A lab has confirmed it contains no harmful substances (CVEs).

- A Safety Seal (Digital Signature): The pharmacist (Kubernetes) checks the seal. If it’s broken, they refuse to dispense it to the patient (Production Server).

As an Architect, your job is to ensure the “medicine” stays sterile from the Lab (CI/CD) to the Patient (Production).

How images move safely from your laptop to the Cloud.

- Docker Hub vs. Private Registries: Why enterprises use Harbor, ECR, or Artifactory.

- Tagging Strategy: Never rely on :latest. Use Semantic Versioning (myapp:1.2.3) or Git Commit SHAs.

- Immutability: Once a version is pushed, it should never be changed.

—

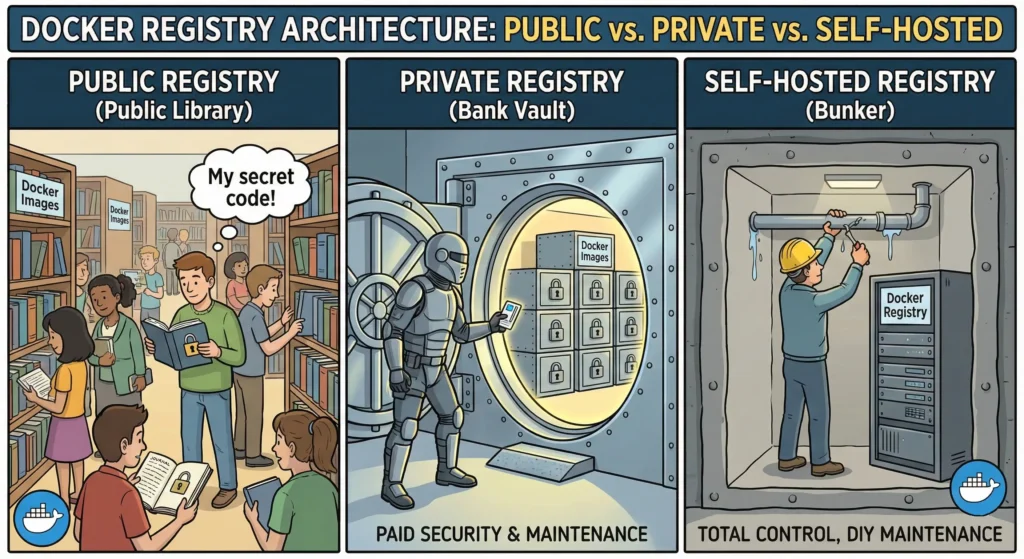

4.1. Registry Architecture: Public vs. Private

Think of a Docker Registry like a Warehouse for your code.

- Public Registry (Public Library): Anyone can walk in and borrow a book. It’s free and has millions of books, but if you leave your personal diary (secret code) there, anyone can read it.

- Private Registry (Bank Vault): You rent a secure vault. Only people with a key (password/token) can enter. You pay for the security and maintenance.

- Self-Hosted Registry (Bunker): You build the vault yourself inside your own basement. You have total control, but if the roof leaks (server crashes), you have to fix it yourself.

A Docker Registry is the server application that stores and distributes Docker images. Choosing the right one is the foundation of your supply chain security.

—

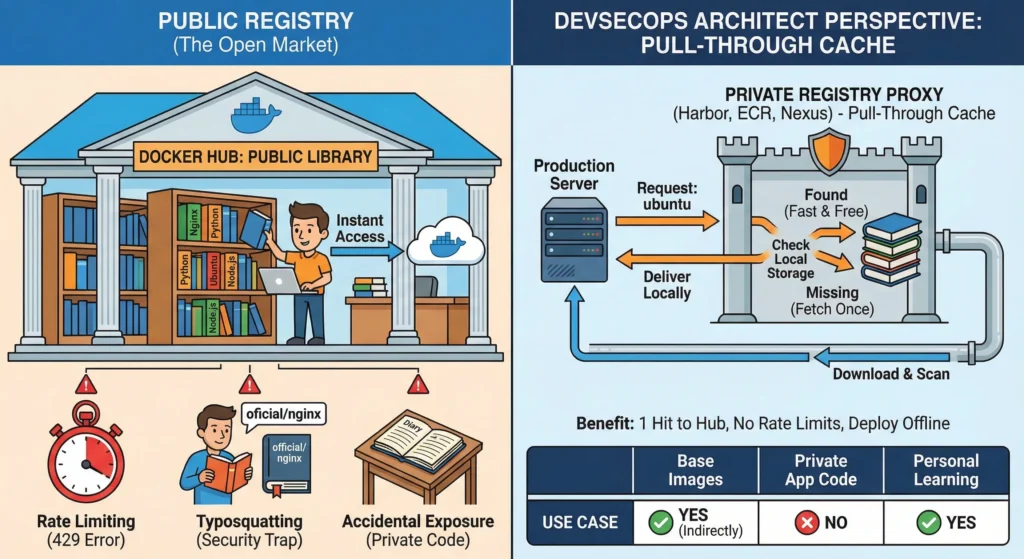

4.1.1. Public Registries (The “Open Market”)

Think of a Public Registry (like Docker Hub) as a massive Public Library.

- Access: It is open 24/7, free to enter, and anyone can walk in and borrow a book (Image).

- Content: It houses millions of standard books like “How to cook” (Nginx), “Learn Math” (Python), or “Basic History” (Ubuntu).

- The Rule: You borrow books from there, but you never leave your personal diary (Source Code) on the table. If you do, anyone can read your secrets.

—

These are massive, shared libraries hosted on the public internet. They are the default place where open-source software lives.

- Examples: Docker Hub (docker.io), http://Quay.io (quay.io), Google Container Registry (gcr.io – public images).

- Pros:

- Instant Access: You don’t need to install an OS from a CD/ISO anymore. You just type FROM ubuntu:22.04, and you have a working server in 5 seconds.

- Community Support: Every major software (Node.js, Postgres, Redis) publishes their “Official Image” here first.

- Cons (The Architect’s Headache):

- Rate Limiting (The “429” Error): Docker Hub enforces a strict “Fair Use” policy.

- Anonymous Users: Limited to 100 pulls per 6 hours.

- Authenticated Free Users: Limited to 200 pulls per 6 hours.

- Impact: If your production cluster tries to auto-scale and pull 500 images at once, Docker Hub blocks you. Your scaling fails, and your website goes down.

- Typosquatting (The Security Trap): Hackers upload malicious images with names that look almost like the real ones.

- Real: official/nginx

- Fake: oficial/nginx (Note the missing ‘f’).

- Result: If a developer makes a typo, they download malware that mines cryptocurrency on your server.

- Accidental Exposure: If you run docker push my-app while logged into Docker Hub, your proprietary code becomes public instantly.

—

DevSecOps Architect Perspective

The “Pull-Through Cache” Pattern (Mandatory for Enterprise)

Never let your production servers pull directly from Docker Hub. It is unreliable and insecure for enterprise scale.

The Solution: Set up a Proxy (Pull-Through Cache) using a private registry tool (like Harbor, AWS ECR, or Nexus).

The Workflow:

- Request: Your Production Server asks your internal Private Registry for ubuntu.

- Check: The Private Registry looks in its local storage.

- Scenario A (Found): It delivers the image locally at Gigabit LAN speeds. (Fast & Free).

- Scenario B (Missing): It goes to Docker Hub once, downloads the image, scans it, saves it, and then delivers it to your server.

- Benefit:

- You only hit Docker Hub 1 time (to fill the cache).

- You never hit Rate Limits.

- If the internet goes down, you can still deploy because you have a local copy.

—

Use Case

| Scenario | Use Public Registry? | Reason |

| Base Images | YES (Indirectly) | Source python, node, alpine from here, but pull them through your Proxy. |

| Private App Code | NO | Never push your company’s banking app or intellectual property here. |

| Personal Learning | YES | Perfect for “Hello World” apps and learning Docker. |

—

—

Technical Challenges

- The “Tag Mutability” Risk:

- In a Public Registry, the author of library/postgres:14 can delete the image and upload a new, broken version with the same tag 10 minutes later.

- Architect’s Fix: Always pin your base images to a specific SHA Digest (e.g., FROM postgres@sha256:abc123…) or mirror them to your private registry where you control the changes.

—

Cheat Sheet

| Feature | Public Registry (Docker Hub) |

| Cost | Free (for public images). |

| Speed | Slow (Dependent on Internet speed). |

| Reliability | Medium (Subject to Rate Limiting). |

| Security | Low (Typosquatting risks, Public exposure). |

| Best For | Sourcing Base Images (FROM …). |

| Golden Rule | “Read Only.” Pull from it, but never Push your secrets to it. |

—

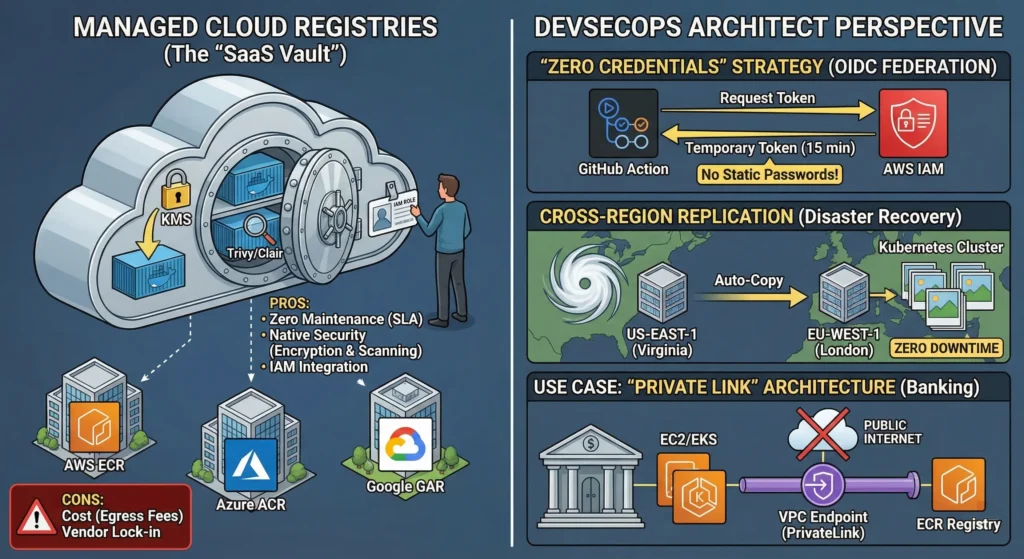

4.1.2. Managed Cloud Registries (The “SaaS Vault”)

The “Rented Bank Vault” Think of this as “Registry as a Service.”

Instead of building a safe in your own house (Self-Hosted), you rent a high-security box inside a massive bank (Cloud Provider like AWS or Google).

You don’t worry about the locks, the guards, or the building collapsing. The bank handles all the maintenance and security. You just show your ID card (IAM Role) to get in.

These are fully managed services provided by cloud giants. You pay them to store and secure your Docker images. They take care of the underlying storage, backups, and patching.

Tools:

- AWS: Elastic Container Registry (ECR)

- Azure: Azure Container Registry (ACR)

- Google: Google Artifact Registry (GAR)

- Pros:

- Zero Maintenance (SLA): No OS patching, no hard drive monitoring. The provider guarantees 99.9% uptime.

- Native Security:

- Encryption: Images are encrypted at rest (e.g., using AWS KMS keys).

- Scanning: Most trigger an automatic vulnerability scan (using engines like Trivy or Clair) the moment an image is uploaded.

- Integration (The “Killer Feature”): It connects natively to the cloud ecosystem using IAM (Identity & Access Management). You don’t need “usernames and passwords.”

- Cons:

- Cost: You pay for storage (per GB) and data transfer (Egress). If you pull a huge image 1000 times to a server outside the cloud, the bill will shock you.

- Vendor Lock-in: Moving 50TB of images from AWS to Azure is slow, expensive, and technically painful.

—

DevSecOps Architect Perspective

As an Architect, you choose Cloud Registries for Identity Security and Resilience.

- The “Zero Credentials” Strategy (OIDC Federation)

- You create a “Service Account,” generate a long-lived password, and save it in Jenkins secrets.

- Risk: If that secret leaks, hackers own your registry.

- The Architect’s Way (IAM Roles): We use OpenID Connect (OIDC).

- Request: Your GitHub Action (Build Job) says: “Hey AWS, I am the ‘Build-Job’ repository. Can I have a temporary key?”

- Verify: AWS checks the trust policy.

- Grant: AWS gives a temporary token valid for only 15 minutes.

- Result: No static passwords exist anywhere. Even if a hacker intercepts the token, it expires before they can use it.

- You create a “Service Account,” generate a long-lived password, and save it in Jenkins secrets.

- Cross-Region Replication (Disaster Recovery) The Scenario: What happens if the AWS us-east-1 (Virginia) region goes offline due to a hurricane?

- You enable Cross-Region Replication on your registry.

- As soon as you push an image to us-east-1, AWS automatically copies it to eu-west-1 (London).

- Your Kubernetes cluster in London keeps pulling images locally without interruption. Zero downtime.

—

Use Case: The “Private Link” Architecture

Scenario: A Banking Application running on AWS.

- Requirement: The bank’s servers (EC2/EKS) must never access the public internet, not even to pull images.

- Solution: Use VPC Endpoints (PrivateLink).

- How it works: The connection between your server and the ECR Registry travels through the AWS internal backbone network, not the public internet. It is faster, more secure, and compliant with banking regulations.

—

—

Technical Challenges

| Challenge | Architect’s Strategic Fix | Why it Matters |

| Cost Explosion | Lifecycle Policies. | Cloud storage is not free. Set a rule: “Delete untagged images after 7 days” or “Delete ‘dev’ tags after 30 days.” This saves 50-70% on the bill. |

| Public Exposure | Block Public Access. | By default, some registries might be public. Enforce an Organization-wide Policy (SCP) that strictly denies public read access to private repos. |

| Slow Pulls (Hybrid) | Local Caching. | If your on-premise servers pull from the Cloud, latency is high. Use a local “Pull-Through Cache” (like Harbor) on-premise to mirror the Cloud Registry. |

—

- AWS ECR: docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonECR/latest/userguide/

- Azure ACR: learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/container-registry/

- Google Artifact Registry: cloud.google.com/artifact-registry/docs

—

Cheat Sheet (Managed Registries)

| Feature | Managed Cloud Registry (ECR/ACR/GAR) |

| Analogy | The Rented Vault. |

| Maintenance | Zero. (Provider handles OS/Storage). |

| Security | High. (Encryption + IAM Roles). |

| Authentication | IAM / OIDC (No static passwords). |

| Cost Model | Pay-per-use (Storage + Data Transfer). |

| Best For | Modern Cloud-Native Startups & Enterprises. |

| Architect’s Tip | Enable Lifecycle Policies immediately to save money. |

—

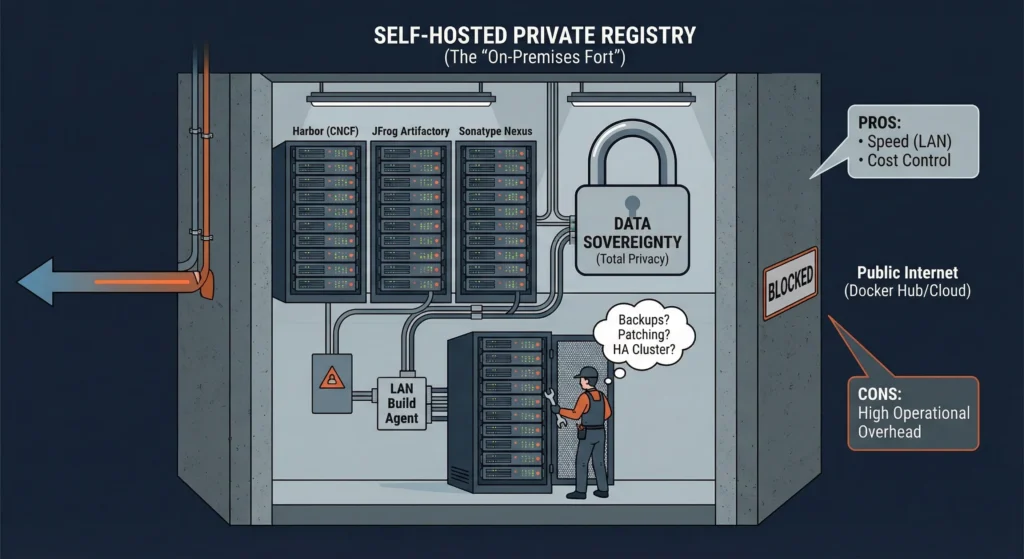

4.1.3. Self-Hosted Private Registries (The “On-Premises Fort”)

The “Underground Bunker” Think of this as building your own high-security bunker.

You don’t trust the public library (Docker Hub) or the rented bank vault (Cloud). You buy your own steel, concrete, and servers. You build the vault inside your own basement.

The Trade-off: You have total control and total privacy. But if the light bulb breaks or the roof leaks, you have to fix it. There is no landlord to call.

You download registry software (like Harbor) and install it on your own servers (Linux or Kubernetes) inside your private data center. You own the hardware, the network cables, and the hard drives.

- Tools:

- Harbor: (The CNCF Standard – Highly Recommended). Open-source, widely used, and feature-rich.

- JFrog Artifactory: The enterprise giant, supports generic binaries too (Maven, NPM).

- Sonatype Nexus: Another popular choice for mixed artifact storage.

- Pros:

- Data Sovereignty (Total Privacy): Your code never touches the public internet. This is mandatory for Banks, Military, and Hospitals (GDPR/HIPAA compliance).

- Speed (LAN vs WAN): Since the server is next to your build agents on the Local Area Network (LAN), pulling a 2GB image takes seconds (Gigabit speeds), unlike pulling from the Cloud which depends on internet bandwidth.

- Cost Control: No “per GB” monthly bill from Amazon. You pay for the hardware once.

- Cons (The “Hidden” Costs):

- High Operational Overhead: “With great power comes great responsibility.” You are responsible for:

- Backups: If the disk fails and you have no backup, the code is gone forever.

- Patching: You must update the OS and Registry software to fix security holes.

- High Availability (HA): If your single server crashes, no one can deploy code. You need to architect complex clusters with load balancers.

- High Operational Overhead: “With great power comes great responsibility.” You are responsible for:

—

—

Technical Challenges

| Challenge | Architect’s Strategic Fix | Why it Matters |

| Garbage Collection | Scheduled GC Windows. | Unlike cloud storage, deleting an image in Harbor doesn’t free up disk space immediately. You must run a “Garbage Collection” job (which often freezes the registry) to reclaim space. |

| Certificate Errors | Distribute Root CA. | Self-hosted registries usually use private SSL certificates. Every Kubernetes node and developer laptop must trust your Root CA, or docker pull will fail with x509 errors. |

| Single Point of Failure | External Database/Redis. | Do not use the default “all-in-one” installation for production. Use an external Postgres and Redis so you can run multiple Harbor nodes for redundancy. |

—

Cheat Sheet: Registry Selection

| Feature | Docker Hub (Public) | AWS ECR (Cloud) | Harbor (Self-Hosted) |

| Role | The “Library” | The “SaaS Vault” | The “Bunker” |

| Best For | Open Source, Base Images | Standard Enterprise Apps | Banks, Gov, Highly Regulated |

| Maintenance | None | Zero (Managed) | High (You manage OS/Storage) |

| Security | Low (Public) | High (IAM Integrated) | Highest (Air-Gap Capable) |

| Speed | Slow (Internet dependent) | Fast (Internal Cloud Network) | Fastest (Local LAN) |

| Cost | Free (mostly) | Pay-as-you-go | CapEx (Hardware/Staff) |

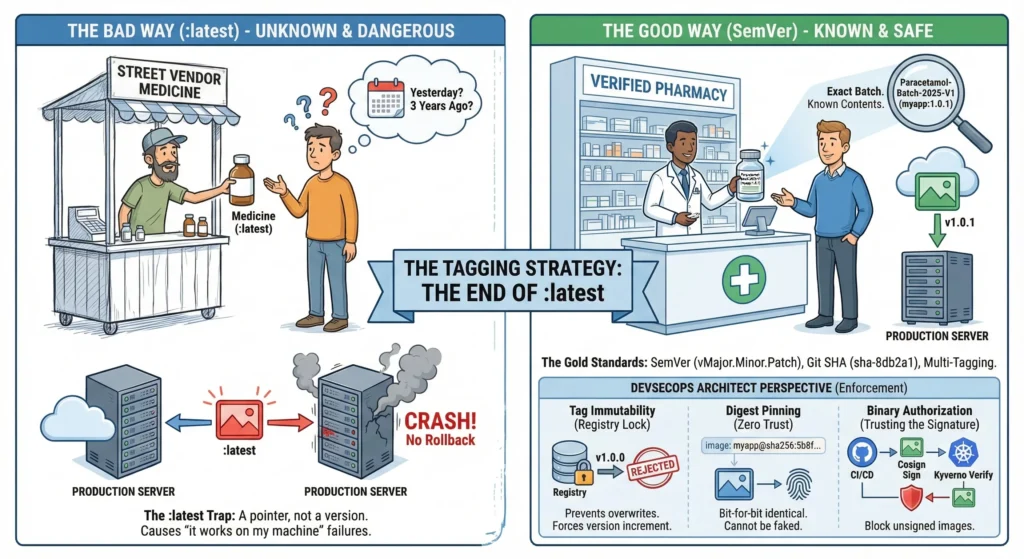

4.2. The Tagging Strategy: The End of :latest

Tagging is the process of giving your Docker image a specific, unchangeable version name so you always know which “batch” of code you are running.

Think of Docker Tags like Batch Numbers on Medicines.

- The Bad Way (:latest): You buy a bottle just labeled “Medicine”. You don’t know if it was made yesterday or 3 years ago. If you buy a second bottle tomorrow, it might have completely different pills inside. This is dangerous.

- The Good Way (SemVer): You buy a bottle labeled “Paracetamol-Batch-2025-V1” (myapp:1.0.1). You know exactly what is inside.

- The Seal (Immutability): If someone tries to open the bottle and swap the pills (overwrite the tag), the seal breaks. The Pharmacist (Kubernetes) checks the seal and refuses to sell it.

Tagging is the process of applying a label to a specific version of your image. It is the only way to distinguish “Code V1” from “Code V2”.

The :latest Trap

Using :latest is the 1st cause of “it works on my machine but breaks in production.”

- It is a Pointer, not a Version. It simply points to the last image pushed.

- The Scenario: You deploy myapp:latest on Friday. It works. On Saturday, a junior dev pushes broken code to myapp:latest. On Sunday, your server restarts, pulls the “new” :latest, and crashes. You have no way to rollback because you don’t know what the previous version was.

The Gold Standards

- Semantic Versioning (SemVer): The Human Standard.

- Format: vMajor.Minor.Patch (e.g., v2.1.0).

- Major: Breaking changes (API changes).

- Minor: New features (Backward compatible).

- Patch: Bug fixes.

- Git Commit SHA: The Machine Standard.

- Format: First 7 chars of Git Hash (e.g., sha-8db2a1).

- Why: It creates a perfect “Audit Trail.” If sha-8db2a1 crashes, you go to GitHub, look up commit 8db2a1, and you see exactly which line of code caused it.

- Multi-Tagging: The Professional Way.

- You tag the same image with both. One for humans to read, one for the machine to audit.

# Tag for Humans (Release Version)

docker tag myapp:build myrepo/myapp:v1.2.3

# Tag for Audit (Code Traceability)

docker tag myapp:build myrepo/myapp:sha-8db2a1

# Push both

docker push myrepo/myapp:v1.2.3

docker push myrepo/myapp:sha-8db2a1

—

DevSecOps Architect Perspective

As an Architect, you don’t trust developers to “remember” not to overwrite tags. You enforce it.

- Tag Immutability (The Registry Lock)

- The Risk: A developer fixes a bug and pushes v1.0.0 again. Now v1.0.0 means two different things. This destroys consistency.

- The Fix: Enable “Tag Immutability” in AWS ECR or Harbor.

- The Effect: If v1.0.0 exists, the registry rejects any push trying to overwrite it. The developer is forced to increment the version to v1.0.1.

- Digest Pinning (Zero Trust / The “Fingerprint”)

- The Concept: A Tag (v1.0) can theoretically be moved. A Digest (sha256:a8f9…) is a mathematical calculation of the image content. It cannot be faked or moved.

- The Strategy: In high-security Production Kubernetes manifests, we do not use tags. We use Digests.

- Risky: image: myapp:v1.2.3

- Secure: image: myapp@sha256:5b8f…

- Result: It ensures that the code running is bit-for-bit identical to the code you tested.

- Binary Authorization (Trusting the Signature)

- We move from “Trusting the Tag” to “Trusting the Signature”.

- Tools: Cosign (Sigstore).

- Workflow:

- Sign: CI Pipeline signs the image: cosign sign –key private.key myapp:v1.0.

- Verify: Kubernetes Admission Controller (Kyverno) checks: “Does this image have a valid signature?”

- Block: If the image was created by a hacker (unsigned), Kubernetes deletes the Pod immediately.

- We move from “Trusting the Tag” to “Trusting the Signature”.

—

—

Technical Challenges

| Challenge | Architect’s Strategic Fix | Why it Matters |

| Image Sprawl | Retention Policies. Auto-delete tags older than 90 days unless they match v* (Release tags). | Prevents storage costs from exploding while keeping important release history safe. |

| Tag Drift | Digest Pinning. Use @sha256:… in production manifests. | Prevents “Supply Chain Attacks” where a hacker replaces a known tag with a malicious image. |

| Supply Chain Poisoning | Vulnerability Gates. Block any tag from being promoted to “Release” if it has Critical CVEs. | Ensures you never “seal” a bottle of medicine that contains poison. |

| Rate Limiting | Pull-Through Cache. Mirror Docker Hub base images internally. | Ensures your builds don’t fail because you downloaded alpine too many times. |

—

- Docker Tagging: docs.docker.com/engine/reference/commandline/tag/

- AWS ECR Immutability: docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonECR/latest/userguide/image-tag-mutability.html

- Cosign (Sigstore): docs.sigstore.dev/cosign/overview/

—

Cheat Sheet: Tagging Strategy

| Concept | Example | Architect’s Verdict |

| Mutable Tag | myapp:latest | BANNED. Unreliable pointer. Never use in Prod. |

| SemVer Tag | myapp:v1.2.0 | GOOD. Great for human communication and Releases. |

| Commit SHA | myapp:sha-8db2a1 | EXCELLENT. Perfect for debugging and traceability. |

| Digest Pin | myapp@sha256:abc… | BEST (Zero Trust). Immutable. Use for Base Images. |

| Multi-Tag | v1.2 + sha-8db | STANDARD. Use both for maximum visibility. |

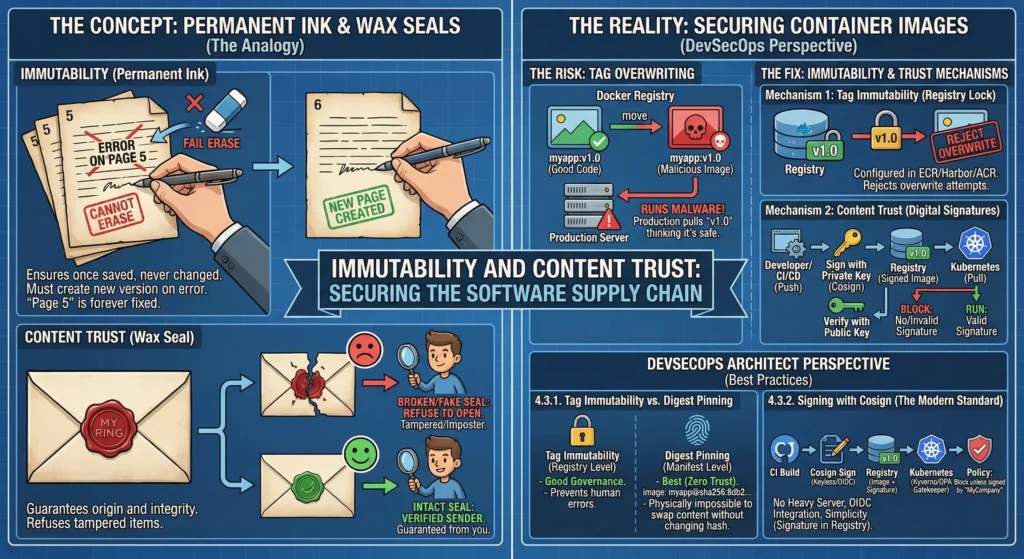

4.3. Immutability and Content Trust

Immutability ensures that once a version of your app is saved, it can never be changed; Content Trust ensures that the app you are downloading is actually the one your team created and signed.

Imagine you are sending a secret letter (Code) to a friend (Server).

- Immutability (Permanent Ink): You write the letter in permanent ink on numbered pages. If you make a mistake on Page 5, you cannot simply erase it and rewrite it. You must create a completely new Page 6. This guarantees that “Page 5” always reads the same way, forever.

- Content Trust (Wax Seal): You place a wax seal with your unique ring on the envelope.

- If the friend receives the letter and the seal is broken (tampered with) or looks fake (wrong signature), they refuse to open it.

- This guarantees the letter actually came from you, not an imposter.

—

Securing the Image: The Risk: Tag Overwriting

- The Problem: By default, Docker tags are mutable (changeable).

- Scenario: You push myapp:v1.0 (Good Code). Later, a hacker (or a buggy pipeline) pushes a malicious image and also tags it myapp:v1.0.

- Result: Docker simply moves the label v1.0 to the bad image. Your production server pulls v1.0 thinking it is the safe version, but runs the malware instead.

- The Fix: We need Immutability.

Mechanism 1: Tag Immutability (The Registry Lock)

- A configuration setting in enterprise registries (AWS ECR, Harbor, Azure ACR).

- You tell the registry: “If a tag named v1.0 already exists, REJECT any attempt to overwrite it.”

Mechanism 2: Content Trust (Digital Signatures)

- Cryptographically signing the container image.

- Sign: When the developer (or CI/CD) pushes code, they sign it with a Private Key.

- Verify: When the server (Kubernetes) tries to pull/run it, it checks the signature against the Public Key.

- Block: No signature? No run.

—

DevSecOps Architect Perspective

4.3.1. Tag Immutability vs. Digest Pinning

Tag Immutability is a good “Governance” policy, but Digest Pinning is the “Zero Trust” technical standard.

- Tag Immutability (Registry Level): Good. Prevents humans from making mistakes.

- Digest Pinning (Manifest Level): Best.

- Concept: Every image has a unique SHA256 Digest (e.g., sha256:8db2…). This is a mathematical hash of the binary content.

- Strategy: In your Kubernetes YAML, do not write image: myapp:v1.2.3. Instead, write image: myapp@sha256:8db2….

- Why: Even if the registry is hacked and the tag is moved, the Digest cannot change. It is physically impossible to swap the image content without changing the hash.

4.3.2. Signing with Cosign (The Modern Standard)

The industry has moved from Docker Content Trust (Notary v1) to Sigstore Cosign.

- Why Architects Prefer Cosign:

- No Heavy Server: Unlike Notary, it doesn’t require managing complex infrastructure.

- OIDC Integration: It supports “Keyless Signing” using your existing identity (GitHub Actions, Google, OIDC).

- Simplicity: It stores the signature in the registry itself (as a separate artifact alongside the image), making it easy to manage.

The Architect’s Workflow:

- CI Build: Pipeline builds the image.

- Sign: Pipeline signs the image: cosign sign –key cosign.key myrepo/app:v1.

- Admission Control: Install Kyverno or OPA Gatekeeper in the Kubernetes cluster.

- Policy: “Block any Pod start request unless the image has a valid signature from ‘MyCompany’.”

—

—

Technical Challenges

| Challenge | Architect’s Strategic Fix | Why it Matters |

| Key Management | Keyless Signing (Sigstore). | Managing private keys (.pem files) is a security nightmare. Keyless signing uses ephemeral certificates tied to your OIDC identity (e.g., “This was signed by the GitHub Actions Runner”). |

| Tag Drift | Digest Pinning. | Tags can be moved by registry admins. Digests are immutable math. Use Digests for base images (FROM python@sha256…) to prevent supply chain poisoning. |

| Vulnerable Base Images | “Scan on Push” Gates. | Prevent a signature from ever being applied if the image has Critical CVEs. A signed image should imply “Secure,” not just “Authentic.” |

| Orphaned Images | Lifecycle Policies. | Immutable tags can pile up. Set rules to delete non-prod tags after 90 days to save storage costs. |

—

- AWS ECR Immutability: docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonECR/latest/userguide/image-tag-mutability.html

- Cosign (Sigstore): docs.sigstore.dev/cosign/overview/

- Harbor Tag Immutability: goharbor.io/docs/2.0.0/administration/configure-tag-immutability/

- Docker Content Trust: docs.docker.com/engine/security/trust/

—

Cheat Sheet: Trust Strategy

| Feature | Concept | Architect’s Verdict |

| Mutable Tag | v1.0 can be overwritten. | Risk. Avoid in production. |

| Immutable Tag | Registry blocks overwrites. | Mandatory for Enterprise Registries. |

| Digest Pinning | image@sha256:… | Zero Trust. The highest security standard. |

| Signing | Digital Wax Seal (Cosign). | Supply Chain Security. Verify origin before running. |

| Policy | “No Signature, No Run.” | Enforcement. Use Admission Controllers (Kyverno). |

4.4. Lab: The Secure Push Workflow

The “Sterile Lab” Protocol Think of this workflow like a Pharmaceutical Lab.

- The Amateur Way: You mix chemicals in a beaker and immediately sell it to patients. If it’s poisonous, people die.

- The Architect’s Way:

- Synthesize (Build): Create the medicine in a sterile environment.

- Lab Test (Scan): Run it through a spectrometer to check for toxins (Vulnerabilities). If toxins are found, destroy the batch.

- Label (Tag): Give it a precise batch number (Version).

- Seal (Sign): Put a tamper-proof seal on the bottle.

- Distribute (Push): Only then ship it to the pharmacy (Registry).

—

Practical Lab: Manual Walkthrough

Prerequisite: You need Docker installed and a Docker Hub account.

Step 1: Authenticate Safely (The Key Card)

Never type your password in the terminal. It gets saved in your shell history (~/.bash_history) where hackers can read it.

- Architect’s Fix: Use a Personal Access Token (PAT).

# Create a file named 'token.txt' with your PAT inside. # The '--password-stdin' flag tells Docker to read from the pipe, not the keyboard. cat token.txt | docker login --username <your_hub_user> --password-stdin

Step 2: Build with Precision (The Batch Number)

Never build without a version. We simulate a release here.

export VERSION=v1.0.5

export IMAGE=myrepo/secure-app

# Build and tag immediately

docker build -t $IMAGE:$VERSION .

Step 3: The Security Gate (The Lab Test)

This is the most critical step. We scan the image locally before it ever leaves our laptop.

- Tool: Trivy (running as a container to scan another container).

- The Logic: We use –exit-code 1. This tells Trivy: “If you find a CRITICAL bug, crash the script (return Error 1).”

docker run --rm \ -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock \ aquasec/trivy image \ --severity CRITICAL \ --exit-code 1 \ $IMAGE:$VERSION # Check the result manually if [ $? -eq 0 ]; then echo "✅ Image is Clean. Proceeding..." else echo "❌ CRITICAL Vulnerabilities found! Push Aborted." exit 1 fi

Step 4: The Push (Shipping)

Only if Step 3 passed do we upload the image.

docker push $IMAGE:$VERSIONStep 5: The Signature (The Wax Seal) – Advanced

Now that the image is in the registry, we sign it to prove ownership.

- Tool: Cosign.

# Sign the uploaded image with your private key cosign sign --key cosign.key $IMAGE:$VERSION

—

DevSecOps Architect Perspective

Why this specific order matters:

- Scan BEFORE Push: Many juniors push first, then scan in the registry.

- The Risk: Once you push, the image is in the cloud. Even if you delete it later, a hacker might have already pulled it.

- The Rule: Shift Left. Scan locally. If it’s dirty, it never leaves your machine.

- Exit Codes: Automation depends on “Exit Codes.”

- Exit Code 0 = Success (Green).

- Exit Code 1 = Failure (Red).

- By using –exit-code 1 in Trivy, we allow Jenkins/GitLab CI to automatically stop the pipeline without human intervention.

—

Technical Challenges

| Challenge | Architect’s Strategic Fix | Why it Matters |

| “Docker Socket” Permission | Use Rootless Podman or Trivy Binary. | Mounting /var/run/docker.sock (as done in Step 3) gives the scanner Root access to your host. In CI/CD, prefer downloading the binary version of Trivy instead of the Docker version. |

| False Positives | .trivyignore file. | Sometimes a scanner flags a “Critical” bug that doesn’t affect your specific app. Create a .trivyignore file to whitelist it so your build passes (but audit it first!). |

| Token Management | External Secrets / Vault. | In this lab, we used a text file. In production, inject secrets using HashiCorp Vault or AWS Secrets Manager directly into the build environment. |

Cheat Sheet (The Workflow Script)

Copy this script to automate your push.

#!/bin/bash

# Architect's Secure Push Script

IMAGE_NAME="myrepo/webapp"

TAG="v1.2.0"

# 1. Build

echo "🔨 Building..."

docker build -t $IMAGE_NAME:$TAG .

# 2. Scan (The Gate)

echo "🔍 Scanning..."

docker run --rm -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock \

aquasec/trivy image --exit-code 1 --severity CRITICAL $IMAGE_NAME:$TAG

# 3. Check Exit Code

if [ $? -ne 0 ]; then

echo "❌ Security Check Failed. Fix vulnerabilities before pushing."

exit 1

fi

# 4. Push

echo "🚀 Security Check Passed. Pushing..."

docker push $IMAGE_NAME:$TAG

echo "✅ Done."