Networking

What is Networking?

At its core, networking is just computers talking to each other. Just like humans need a language to speak and ears to listen, computers need cables (or Wi-Fi) and protocols (rules) to share information.

- Your laptop sends a “Request“.

- Google’s server sends a “Reply“.

- This round trip is Networking.

Think as: The Indian Postal System.

- Data/Packet: The letter inside the envelope.

- Cable/Wi-Fi: The road or train track the postman uses.

- IP Address: The address written on the envelope (e.g., “M.G. Road, Bengaluru”).

- Router: The local post office that decides which direction to send the mail next.

Networking is the practice of transporting data between devices. In the modern world, this isn’t just about two laptops connected by a wire. It involves:

- Sharing Data: Sending files, emails, or watching YouTube.

- Resource Sharing: Multiple office computers using one printer.

- The Internet: The biggest Wide Area Network (WAN) in the world.

Key Components:

- Client: The device asking for info (your mobile).

- Server: The device giving info (Google server).

- Medium: How they connect (Fiber optic, Wi-Fi).

Networking is the foundation of Distributed Systems. We don’t just “connect cables”; we design resilient communication fabrics.

- Software Defined Networking (SDN): We no longer manually configure routers physically. We use code (Infrastructure as Code) to manage networks.

- Overlay Networks: In Kubernetes, we create a “virtual network” on top of the physical network so containers can talk to each other easily.

—

Use Case

Scenario: A startup in Hyderabad wants to host a secure e-commerce website.

- Networking Role: It allows customers from Mumbai to connect to the servers in Hyderabad securely using HTTPS, while the payment gateway talks to the bank over a private secure channel.

Benefits

- Connectivity: Global reach for applications.

- Centralization: Manage data in one place (Cloud) and access it from anywhere.

Technical Challenges

- Latency: The time it takes for data to travel (lag).

- Congestion: Too much traffic slowing down the network (like traffic jams on Silk Board junction).

- Issue: “The website is slow.”

- Solution: Use a CDN (Content Delivery Network) like Cloudflare to cache content closer to the user.

| Type | Full Form | Scope | Real-Life Example |

| LAN | Local Area Network | Small (Building) | Your Office Wi-Fi or Home Router. |

| WAN | Wide Area Network | Global | The Internet / 4G / 5G. |

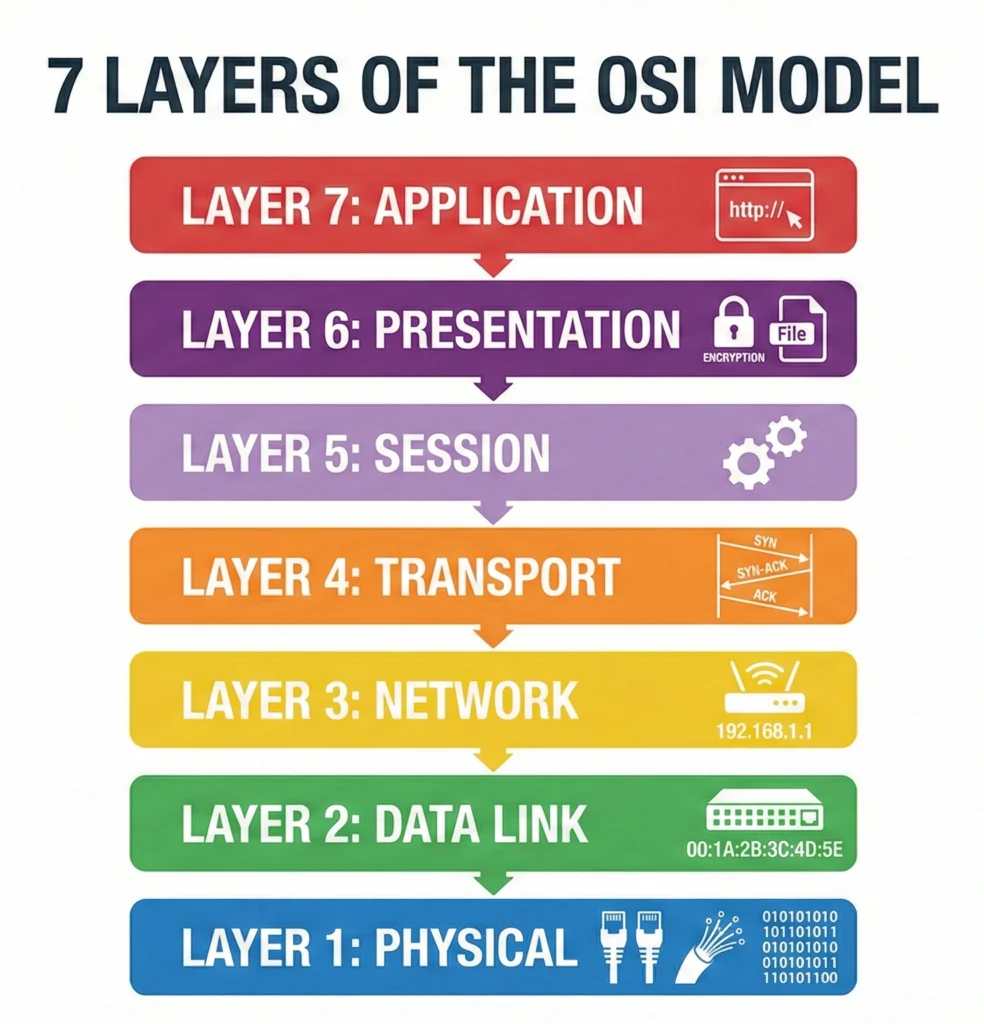

The OSI Model

The OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model is a conceptual framework. It explains how data travels from your screen, through the wire, to a server, and back. It breaks this complex journey into 7 Layers.

Memory Trick to remember layers (Bottom to Top): Please Do Not Throw Sausage Pizza Away (Physical, Data Link, Network, Transport, Session, Presentation, Application)

Think as: Ordering a Pizza Online.

- Application (Layer 7): You look at the menu on the app (User Interface).

- Presentation (Layer 6): The app translates your tap into data and encrypts your payment (Translation/Security).

- Session (Layer 5): The app keeps your connection open while you order (Conversation control).

- Transport (Layer 4): The order is checked to ensure all items are listed correctly. If an item is missing, they ask again (Reliability/TCP).

- Network (Layer 3): The delivery guy uses GPS to find your house address (IP Addressing/Routing).

- Data Link (Layer 2): The delivery guy drives his bike on the specific road to your gate (MAC Address/Switching).

- Physical (Layer 1): The actual bike and the road (Cables/Hardware).

Here is what happens at each layer:

- Layer 7 – Application: What the user sees (Browser, HTTP, SMTP for email).

- Layer 6 – Presentation: Formatting and Encryption (SSL/TLS). It ensures data is readable.

- Layer 5 – Session: Manages the session between two computers (Login/Logout).

- Layer 4 – Transport: Decides how much data to send. Uses TCP (Reliable) or UDP (Fast).

- Layer 3 – Network: Logical Addressing (IP Address). Routers operate here.

- Layer 2 – Data Link: Physical Addressing (MAC Address). Switches operate here.

- Layer 1 – Physical: The actual bits (0s and 1s) traveling over copper wire or fiber.

—

As an architect, you map these layers to security and cloud components:

- L7 (Application): WAF (Web Application Firewall), Ingress Controllers in Kubernetes.

- L4 (Transport): Network Load Balancers, TCP proxying.

- L3 (Network): VPC (Virtual Private Cloud), Security Groups, Route Tables.

- L2 (Data Link): ARP (Address Resolution Protocol), Virtual Network Interfaces (ENI).

Architect Insight: When debugging a “Connection Refused” error:

- Check L3 (Security Groups/Firewalls).

- Check L4 (Is the service listening on that port?).

- Check L7 (Is the application crashing?).

—

Use Case

Scenario: You are securing a Banking App.

- You use HTTPS (Layer 7) for secure user access.

- You use a Stateful Firewall (Layer 3/4) to block bad IP addresses.

- You use VLANs (Layer 2) to separate the Finance department network from the Guest Wi-Fi.

Benefits

- Troubleshooting: If internet works but a website doesn’t load, you know it’s likely an L7 or DNS issue, not L1 (cable).

- Standardization: Different vendors (Cisco, Juniper, AWS) can work together because they follow the same model.

Technical Challenges

- Encapsulation Overhead: Every layer adds a “Header” (extra data). Too many layers can slow down performance slightly.

- Complexity: Debugging cross-layer issues (e.g., an MTU mismatch at Layer 2 causing packet drops at Layer 3) is difficult.

- Issue: “My application is timing out.”

- Solution: Check the MTU (Maximum Transmission Unit). If a packet is too big for the Layer 2 interface, it gets dropped.

Cheat Sheet

| Layer # | Layer Name | Data Unit | Device/Protocol | DevOps Relevance |

| 7 | Application | Data | Browser, HTTP, DNS | Load Balancer (ALB), Ingress |

| 6 | Presentation | Data | SSL/TLS, JPEG | Encryption Keys |

| 5 | Session | Data | APIs, Sockets | Auth Sessions |

| 4 | Transport | Segment | TCP, UDP | Ports, NLB |

| 3 | Network | Packet | Router, IP | VPC, Security Groups |

| 2 | Data Link | Frame | Switch, MAC | CNI Plugins |

| 1 | Physical | Bit | Cable, Hub | Data Center Hardware |

TCP/IP Model

If the OSI Model is a strict 7-step classroom rulebook, the TCP/IP Model is the practical 4-step guide used in the real world.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) created it to ensure that the network could survive even if parts of it were destroyed (like in a war). It simplifies the process by grouping similar OSI layers together.

- OSI = 7 Layers (Too detailed).

- TCP/IP = 4 Layers (Just enough).

The TCP/IP model condenses the 7 OSI layers into 4 broad layers. This is what you will see in Linux networking logs.

The Mapping (Memorize This):

| TCP/IP Layer | OSI Layers Included | What it does? | Key Protocols |

| 1. Application | Application (7), Presentation (6), Session (5) | Handles the data, encryption, and user interface. | HTTP, HTTPS, SSH, DNS |

| 2. Transport | Transport (4) | Ensures data arrives reliably (TCP) or fast (UDP). | TCP, UDP |

| 3. Internet | Network (3) | Moves packets from Source IP to Dest IP. | IP, ICMP, ARP |

| 4. Network Access | Data Link (2), Physical (1) | The physical hardware and MAC addressing. | Ethernet, Wi-Fi, Fiber |

IP Addressing (IPv4)

Every device on a network needs an address so others can find it. An IP (Internet Protocol) Address is just like your home address or mobile number.

Currently, we mostly use IPv4 (Version 4), which looks like 192.168.1.1. (Note: IPv6 exists because we ran out of IPv4 addresses, but IPv4 is still the king in most internal company networks).

Think as: Landline Numbers.

- Public IP: Your main landline number that anyone in the world can call.

- Private IP: Like an Intercom extension number in a big office (e.g., “Dial 402 for reception”).

- People outside the office cannot dial “402” to reach you directly. They call the main office number (Public IP), and the operator connects them to extension 402 (NAT).

An IPv4 address is 32 bits long, divided into 4 parts called octets (e.g., 192 . 168 . 1 . 10).

Key Concept: Private vs. Public IPs This is the most critical concept for beginners.

| Type | Range Example | Where it is used? | Cost |

| Public IP | 8.8.8.8 (Google) | On the Internet. Reachable by anyone. | AWS/Azure charge money for this! |

| Private IP | 192.168.x.x | Inside your Home/Office/VPC. | Free. Secure. Not visible to the internet. |

The 3 Golden Rules of Private IPs (RFC 1918):

- Class A:

10.0.0.0to10.255.255.255(Used in big companies/AWS VPCs). - Class B:

172.16.0.0to172.31.255.255(Used in Docker/AWS). - Class C:

192.168.0.0to192.168.255.255(Used in Home Wi-Fi).

DevSecOps Architect Level

As an Architect, you plan the IP Schema. If you pick the wrong range at the start, you will face “IP Overlap” issues later when connecting two clouds (e.g., AWS to On-Premises).

Architectural Best Practice:

- Never use default IP ranges (like

192.168.0.0/16) for enterprise VPCs because almost every home router uses it. If a developer tries to VPN in from home, their home IP might clash with the server IP. - Recommendation: Use a unique slice of

10.x.x.xfor your Production environment.

Visual Subnet Calculator (A lifesaver for planning VPCs).

Technical Challenges

- IP Exhaustion: Running out of IPs in a subnet. If you create a Kubernetes cluster with a small subnet, you can’t add more pods later.

- IP Conflicts: Two devices having the same IP causes connection drops.

- Issue: “I cannot peer my AWS VPC with my Azure VNet.”

- Solution: Check for Overlapping CIDRs. If both use

10.0.0.0/16, they cannot talk. You must re-create one network with a different range.

Subnetting

Subnetting is simply cutting a big network into smaller pieces.

Why?

- Security: You don’t want the HR department’s printer on the same network as the Finance server.

- Organization: It keeps things tidy (e.g., Ground floor network, First floor network).

We use CIDR (Classless Inter-Domain Routing) notation. It looks like 10.0.0.0/24. The number after the slash / tells you how many IPs you get.

The Easy Cheat Sheet for DevOps: Memorize these three. You will use them 90% of the time.

- /32 = 1 IP (Used for a specific host, e.g., in Firewall rules).

- /24 = 256 IPs (Standard size for a small team/subnet. Usable: 254).

- /16 = 65,536 IPs (Standard size for a whole VPC/Network).

How it works (The Math made simple): Total IPs = 2(32−CIDR)

- Example: /24

- 32−24=8

- 28=256 IPs.

- Example: /28 (Small subnet for specific tools)

- 32−28=4

- 24=16 IPs.

DevSecOps Architect Level

In Cloud (AWS/Azure/GCP), 5 IPs are reserved in every subnet! If you calculate 256 IPs for a /24, you actually only get 251 usable IPs.

Reserved IPs in AWS:

x.x.x.0: Network Address.x.x.x.1: VPC Router.x.x.x.2: DNS Server.x.x.x.3: Future Use.x.x.x.255: Broadcast Address.

Architect Tip: Always over-provision your subnets for Kubernetes (EKS/AKS). Pods consume IPs very fast. A /24 subnet (250 IPs) can fill up with just 50 Nodes if each node runs many pods!

Cheat Sheet: Common CIDR Sizes

| CIDR | Total IPs | Usable (Cloud) | Use Case |

| /32 | 1 | 1 | Single IP in Firewall Rule |

| /28 | 16 | 11 | Very small specific service |

| /24 | 256 | 251 | Standard Subnet |

| /20 | 4,096 | 4,091 | Large Subnet (EKS Clusters) |

| /16 | 65,536 | 65,531 | Entire Virtual Cloud (VPC) |

Routing

Routing is the process of selecting a path for traffic. If the IP address is the “Destination Address,” then the Router is the Google Maps/GPS that decides which road to take to get there.

Computers are dumb; they don’t know where “https://www.google.com” is. They just send the packet to the nearest Router (Gateway) and ask, “You handle this.”

Think as: Airline Travel.

- Packet: You (the passenger).

- Router: The Airport Hub (e.g., Dubai Airport).

- Routing Table: The Flight Display Board showing destinations.

- Hop: Flying from Mumbai → Dubai → London. Each stop is a “Hop”.

—

A Router is a Layer 3 device that connects different networks together (e.g., your Home LAN to the ISP’s WAN).

The Route Table: Every computer and router has a “Route Table.” It’s a simple list of rules:

- “If destination is X, send to Gateway Y.”

- “If I don’t know the destination, send to Default Gateway (0.0.0.0/0).”

Types of Routing:

- Static Routing: You manually type the path. (Simple, but hard to manage for big networks).

- Dynamic Routing: Routers talk to each other and find the best path automatically using protocols like OSPF or BGP.

- Efficiency: Dynamic routing finds the fastest path. If one cable is cut, it automatically reroutes traffic via another cable.

—

Cheat Sheet: Routing Terms

| Term | Meaning | Simple Explanation |

| Gateway | Entry/Exit Point | The door to leave your current network. |

| Hop | Jump | Moving from one router to another. |

| TTL | Time To Live | A timer to kill a packet if it gets lost in a loop. |

| Next Hop | Next Router | “I don’t know the full path, but pass it to HIM, he knows.” |

| 0.0.0.0/0 | Default Route | “Anywhere else” (The Internet). |

NAT: Network Address Translation

NAT is the “Mask” or “Translator.” It allows many devices with Private IPs to browse the internet using a single Public IP.

Without NAT, we would have run out of IPv4 addresses 20 years ago!

Think as: An Office Receptionist.

- You (Private Employee) want to call a client.

- You dial out. The client sees the Office Main Number on their Caller ID, not your desk extension.

- When the client calls back, they call the Main Number, and the Receptionist (NAT) connects them to you.

There are two main types of NAT you must know:

- SNAT (Source NAT): Used when Internal devices start the connection (e.g., You browsing Google from office Wi-Fi). The router changes your Private IP to its Public IP so Google can reply.

- DNAT (Destination NAT): Used when External users want to reach a server inside (e.g., Hosting a web server). This is often called Port Forwarding.

—

DevSecOps Architect Level

In Cloud (AWS), NAT Gateways are critical, but expensive components.

- High Availability: A NAT Gateway in AWS is tied to a specific Availability Zone (AZ). If that AZ goes down, your internet breaks.

- Architectural Rule: For high availability, always deploy one NAT Gateway per AZ.

Security Implication:

- Private Subnets + NAT Gateway = Best Practice.

- Why? Because NAT allows the server to go out (download updates), but prevents the internet from coming in (initiating a connection). It acts like a one-way mirror.

—

Use Case

Scenario: Running a Database Server.

- You never want your Database to have a Public IP.

- But the DB needs to download security patches from the internet.

- Solution: Put DB in Private Subnet. Route traffic through a NAT Gateway.

Benefits

- IP Conservation: You can have 100 computers in an office using just 1 Public IP.

- Privacy: Hides internal network structure from the outside world.

Technical Challenges

- NAT Limits: A NAT device can only handle a certain number of concurrent connections (usually 65,000 ports). If you exceed this, you get “Port Exhaustion” and connections drop.

- Issue: “My connection to the database times out after 1 minute of idleness.”

- Solution: NAT Gateways often have an Idle Timeout. You need to enable “TCP Keepalives” in your application code to keep the connection alive.

Cheat Sheet: NAT Types

| Type | Full Name | Direction | Use Case |

| SNAT | Source NAT | Inside → Out | Office employees browsing the web. |

| DNAT | Destination NAT | Outside → In | Hosting a game server or web server. |

| PAT | Port Address Translation | Many → One | The most common form (Home Wi-Fi). |

DNS: Domain Name System

DNS turns human-readable names (like google.com) into computer-readable IP addresses (like 142.250.193.206).

Computers don’t understand words; they only understand numbers. When you type a website name, your computer secretly asks a DNS server, “What is the number for this name?”

Think as: Your Mobile Phone’s Contact List.

- You don’t memorize your friend’s 10-digit mobile number.

- You just tap “Rajkumar”.

- Your phone (DNS) looks up “Rahul” and dials

987654321x (IP Address).

—

The DNS system is a hierarchy. It’s not just one server; it’s a global chain of servers.

The 4 Key Players:

- DNS Recursor (ISP): The librarian who takes your request and goes to find the answer.

- Root Nameserver (.): The boss at the top. It knows where the

.com,.org,.inservers are. - TLD Nameserver (Top Level Domain): The manager of

.com. It knows wheregoogle.comis. - Authoritative Nameserver: The final destination. It actually holds the IP address for

google.com.

—

DevSecOps Architect Level

As an Architect, DNS is your primary tool for Traffic Management and Disaster Recovery.

Key Records Types:

- A Record: Name → IPv4 (

example.com→1.2.3.4). - AAAA Record: Name → IPv6.

- CNAME (Canonical Name): Name → Another Name (

www.example.com→example.com). Note: Cannot be used at the root domain (APEX). - NS (Name Server): Points to the authoritative server (e.g., AWS Route53).

- MX (Mail Exchange): Directs email to mail servers.

Architect Insight: In AWS Route53, we use Alias Records instead of CNAMEs for the root domain because Alias records are faster and free (internal AWS lookup).

—

Use Case

Scenario: Blue/Green Deployment.

- You have a new version of your app (Green) ready on a new Load Balancer.

- Instead of downtime, you update the DNS Record to point from the Old Load Balancer (Blue) to the New Load Balancer (Green).

- Result: Users are instantly switched to the new app with zero downtime.

Benefits

- Load Balancing: DNS can send 50% traffic to India and 50% to USA servers (Geolocation Routing).

- Human Friendly: Nobody can remember IPs.

Technical Challenges

- Propagation Delay: When you change a DNS record, it can take up to 48 hours to update globally because ISPs cache (save) the old result.

- DNS Spoofing: Hackers tricking your computer into thinking

bank.comis their fake IP.

Common Issues & Solutions

- Issue: “I updated the website IP, but I still see the old site.”

- Solution: This is a TTL (Time To Live) issue. Flush your local DNS cache (

ipconfig /flushdnson Windows) or wait for the TTL to expire.

Cheat Sheet: DNS Records

| Record | Stands For | Function | Example |

| A | Address | Name → IPv4 | blog.com → 1.2.3.4 |

| AAAA | Quad A | Name → IPv6 | blog.com → 2001:db8::1 |

| CNAME | Canonical Name | Name → Name | www.blog.com → blog.com |

| MX | Mail Exchange | Email routing | mail.blog.com |

| TXT | Text | Verification/Security | SPF/DKIM records |

HTTP & HTTPS

HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) is the language computers use to ask for websites. HTTPS is the same language, but Secure (Encrypted).

- HTTP: Sending a postcard (Anyone can read it).

- HTTPS: Sending a letter in a locked steel briefcase (Only the receiver has the key).

Think as: A Customer in a Restaurant.

- You: Client (Browser).

- Waiter: HTTP Request (GET/POST).

- Chef: Server.

- Food: HTTP Response (HTML/JSON).

- Menu: API Documentation.

Every interaction on the web has a Request and a Response.

Common Methods (Verbs):

- GET: “Give me data” (Loading a page).

- POST: “Take this data” (Submitting a login form).

- PUT: “Update this data” (Changing your profile photo).

- DELETE: “Remove this data” (Deleting a post).

Status Codes (The Server’s Reply):

- 200 OK: Success!

- 301/302: Redirect (Go somewhere else).

- 404: Not Found (Wrong URL).

- 403: Forbidden (You don’t have permission).

- 500: Internal Server Error (The server crashed/code broke).

DevSecOps Architect Level

The shift to HTTPS (TLS/SSL) is non-negotiable today.

The SSL Handshake (Simplified):

- Client Hello: “I want to talk securely. Here are the ciphers (locks) I support.”

- Server Hello: “Okay, let’s use this lock. Here is my Certificate (ID Card).”

- Verification: Browser checks if the Certificate is valid (issued by a trusted Authority).

- Key Exchange: They create a temporary “Session Key” to encrypt future data.

Architect Insight: SSL Termination (Offloading): Decrypting HTTPS takes CPU power. In large architectures, we let the Load Balancer handle the decryption (Termination) so the backend servers just focus on the app logic (sending plain HTTP internally).

Cheat Sheet: Status Codes

| Code Range | Meaning | Example |

| 1xx | Informational | 100 Continue |

| 2xx | Success | 200 OK, 201 Created |

| 3xx | Redirection | 301 Moved Permanently |

| 4xx | Client Error | 404 Not Found, 401 Unauthorized |

| 5xx | Server Error | 500 Internal Error, 503 Unavailable |

Firewalls

A Firewall is a security guard that stands between your computer and the internet. It checks every packet of data trying to enter or leave.

- Allow: “You are safe, go inside.”

- Deny: “You look suspicious, get out.”

Think as: A Bouncer at a Club.

- The Club: Your Server/Network.

- The Bouncer: The Firewall.

- The Guest List: The Firewall Rules (e.g., “Only people with ID from India allowed”).

Firewalls work on Rules. A rule usually looks like:

- Source: IP 1.2.3.4

- Destination: Port 80 (Web)

- Action: ALLOW

Types of Firewalls:

- Software Firewall: Runs on your laptop (e.g., Windows Defender).

- Hardware Firewall: A physical box in a server room (e.g., Cisco ASA).

- Cloud Firewall: Virtual firewalls in AWS/Azure (Security Groups).

VPNs & Tunneling

The Internet is a public road. Everyone (hackers, ISPs) can see the cars driving by. A VPN (Virtual Private Network) builds a secret, underground tunnel beneath the public road. When you drive inside the tunnel, no one outside can see you or your cargo.

Think as: A Safe Pipe.

- Imagine sending water (data) through a river (internet). The water gets mixed up.

- Now, imagine laying a steel pipe (VPN) inside the river. The water inside the pipe travels through the river but never touches it.

DevSecOps Architect Level

VPNs use Encryption (IPsec or SSL) to wrap your data packets.

Two Main Types:

- Site-to-Site VPN: Connects a Corporate Office to the Cloud (AWS VPC). It looks like one big continuous network.

- Client-to-Site (Remote Access) VPN: Allows an employee working from home (Starbucks Wi-Fi) to securely access the office server.

Alternatives:

- AWS Direct Connect / Azure ExpressRoute: A dedicated physical fiber cable from your office to the Cloud provider. It bypasses the internet entirely (More secure, expensive).

Network Performance Metrics

Key Terms

- Latency: The delay. How long it takes for a packet to go A → B. (High latency = Lag).

- Bandwidth: The width of the pipe. Maximum data you can send per second.

- Throughput: The actual data being sent right now.

- Jitter: The variation in latency. (Bad for VoIP/Zoom calls).

Think as: A Water Pipe.

- Bandwidth: The diameter of the pipe.

- Throughput: How much water is actually flowing.

- Latency: How fast a drop of water travels from one end to the other.

Important Protocols: SSH, DHCP, FTP, SMTP

Protocols are just “rules of behavior.” If Networking is a society, protocols are the different jobs people do.

- SSH: The Security Guard who lets you into the building.

- DHCP: The Front Desk Officer who gives you a visitor badge (IP address).

- FTP: The Moving Company that transports heavy boxes (files).

- SMTP: The Postman who delivers letters (emails).

Think as: Hotel Staff.

- DHCP (Receptionist): You check in. You don’t pick your room number; the receptionist assigns you Room 101 (IP Address) for 2 days (Lease Time).

- SSH (Key Card): You want to enter your room. You need a verified Key Card (Private Key) that matches the lock (Public Key).

- SMTP (Room Service): You fill out a form to send a request (Email) to the kitchen.

Cheat Sheet: Protocol Ports

| Protocol | Full Name | Port | Transport | OSI Layer | Secure? | DevOps Use Case (Real World) |

| FTP | File Transfer Protocol | 21 | TCP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | Avoid this. Used for uploading files. Sends passwords in plain text. |

| SSH | Secure Shell | 22 | TCP | L7 (App) | ✅ Yes | Daily Driver. Used to log into Linux servers (EC2) securely. Replaces Telnet/FTP. |

| SFTP | Secure FTP | 22 | TCP | L7 (App) | ✅ Yes | Transferring files securely over SSH. |

| TELNET | Teletype Network | 23 | TCP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | Never use for login. Only use for testing connectivity (e.g., telnet google.com 80). |

| SMTP | Simple Mail Transfer | 25 | TCP | L7 (App) | ⚠️ Mixed | Sending Emails. AWS blocks port 25 to stop spam. Use port 587 (TLS) for apps. |

| DNS | Domain Name System | 53 | UDP/TCP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | Critical. Maps google.com → IP. If this fails, your whole cluster can’t talk to the world. |

| DHCP | Dynamic Host Config | 67/68 | UDP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | Automation. Automatically assigns IPs to laptops or servers when they boot up. |

| TFTP | Trivial FTP | 69 | UDP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | Used for booting diskless servers (PXE Boot) in data centers. |

| HTTP | HyperText Transfer | 80 | TCP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | Standard web traffic. Always redirect this to Port 443. |

| POP3 | Post Office Protocol | 110 | TCP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | receiving emails (downloads to device). Rarely used now; IMAP is better. |

| NTP | Network Time Protocol | 123 | UDP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | Syncing Time. Crucial for Logs! If Server A and Server B have different times, debugging is impossible. |

| IMAP | Internet Message Access | 143 | TCP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | Receiving emails (synced across devices). |

| SNMP | Simple Network Mgmt | 161 | UDP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | Monitoring. Used by tools (Nagios/Datadog) to check if a Router/Switch is overheating or full. |

| BGP | Border Gateway Protocol | 179 | TCP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | Routing. The protocol of the Internet. Used to route traffic between ISPs or AWS Direct Connect. |

| HTTPS | HTTP Secure | 443 | TCP | L7 (App) | ✅ Yes | Standard. The secure lock icon 🔒. Encrypts data using TLS/SSL. |

| SMB | Server Message Block | 445 | TCP | L7 (App) | ⚠️ Mixed | Windows File Sharing. Common target for Ransomware (WannaCry). |

| LDAP | Lightweight Directory | 389 | TCP | L7 (App) | ❌ No | User Management (Active Directory). Use LDAPS (636) instead. |

| RDP | Remote Desktop Protocol | 3389 | TCP | L7 (App) | ⚠️ Mixed | Logging into Windows Servers (GUI). Always protect this with a VPN. |

TCP vs UDP: Reliability vs Speed

At the Transport Layer (Layer 4), you have two main choices for sending data:

- TCP (Transmission Control Protocol): The “Reliable” one. It cares about accuracy. It guarantees that the data arrives in perfect order, with no errors.

- UDP (User Datagram Protocol): The “Fast” one. It cares about speed. It sends data instantly without checking if it arrived.

Think as: Registered Post vs. Live Cricket Commentary.

- TCP (Registered Post): You send an important legal document. You pay extra for a “tracking number” and “signature on delivery.” If the letter gets lost, the post office must resend it. It is slower, but guaranteed.

- UDP (Live Cricket Commentary on Radio): The commentator speaks fast. If you miss one word because of static noise, he doesn’t stop to repeat it. He just keeps talking. It is real-time, but if you miss a bit, it’s gone.

—

The main technical difference is the Connection.

- TCP is “Connection-Oriented”: Before sending data, it establishes a connection (The Handshake). It numbers every packet (1, 2, 3…) so they can be reassembled in order.

- UDP is “Connectionless”: It just fires packets at the destination IP. It doesn’t care if the server is ready or if the packets arrive out of order (2, 1, 3…).

The TCP 3-Way Handshake (The “Hello” Process): Before TCP sends a single bit of real data, it does this:

- SYN (Synchronize): Client says, “Hello, can we talk?”

- SYN-ACK (Synchronize-Acknowledge): Server says, “Yes, I heard you (ACK), and I am ready (SYN).”

- ACK (Acknowledge): Client says, “Great, let’s start.”

—

Use Case

Scenario: A Banking App vs. YouTube.

- Banking App (TCP): When you transfer ₹5000, the app uses TCP/HTTPS. If the internet drops for a second, the app pauses and retries until it gets a confirmation. It cannot afford to lose the “Transfer” packet.

- YouTube (TCP/UDP): The video player buffers content using TCP (to ensure quality), but live streaming protocols often prefer UDP-like behavior to keep up with the live event.

—

Cheat Sheet: TCP vs UDP

| Feature | TCP (Transmission Control) | UDP (User Datagram) |

| Connection | Connection-Oriented (Handshake) | Connectionless (Fire & Forget) |

| Reliability | Guaranteed Delivery | Best Effort (No Guarantee) |

| Ordering | 1, 2, 3 (Strict Order) | 1, 3, 2 (Any Order) |

| Speed | Slower (Overhead) | Faster (Low Overhead) |

| Headers | Heavy (20 Bytes) | Lightweight (8 Bytes) |

| Examples | HTTP, HTTPS, SSH, FTP, Email | DNS, DHCP, VoIP, Gaming |

Good to Know Topics

Proxy Servers: The Middleman

A Proxy is a middleman. Instead of connecting directly to a server, you connect to the proxy, and the proxy connects to the server for you.

- No Proxy: You → Google.

- With Proxy: You → Proxy → Google.

- Forward Proxy (The Manager acting for the Celebrity): The Celebrity (You) wants to buy a coffee but doesn’t want to be seen. The Manager (Proxy) goes to the shop, buys it, and brings it back. The shopkeeper sees the Manager, not the Celebrity.

- Reverse Proxy (The Receptionist): You call a big company’s main number. The Receptionist (Proxy) answers and forwards your call to the Support Team (Server). You don’t know the direct number of the Support Team; you only know the main company number.

—

There are two main directions a proxy can work:

- Forward Proxy: Sits in front of the Client.

- Goal: Protects the User.

- Example: Your college Wi-Fi blocking “Facebook”. You are trying to go out, but the proxy stops you.

- Reverse Proxy: Sits in front of the Server.

- Goal: Protects the Server.

- Example: Google has thousands of servers. You hit one URL (

google.com), and a Reverse Proxy decides which server actually handles your request.

Use Case

- Reverse Proxy (Nginx): The public hits

bank.com. Nginx checks security headers and forwards traffic to the App Server. - Forward Proxy (Squid): The App Server needs to update its antivirus. It cannot go to the internet directly. It asks the Squid Proxy, “Please fetch updates from

antivirus.com.”

Benefits

- Anonymity: Hides the IP address of the client (Forward) or the server (Reverse).

- Security: Blocks malicious traffic before it hits the database.

- Performance: Drastically reduces load via Caching.

Technical Challenges

- Single Point of Failure: If the Nginx Reverse Proxy goes down, the entire website is down, even if the 10 backend servers are healthy.

- Solution: Use a Load Balancer in front of the Proxies.

- “Proxy Hell”: In corporate networks, setting environment variables (

HTTP_PROXY,HTTPS_PROXY,NO_PROXY) specifically for Docker, Java, and Python can be a nightmare.

—

Practical Labs

Lab: Setup a Simple Nginx Reverse Proxy (Prerequisite: A Linux VM).

1: Install Nginx:

sudo apt install nginx2: Create a Dummy App: Run a simple python server on port 8000:

python3 -m http.server 80003: Configure Nginx:

#Edit

sudo vim /etc/nginx/sites-available/default.

location / {

proxy_pass http://localhost:8000;

}4: Test: Visit http://localhost:80. You will see the content from Port 8000! Nginx is forwarding it.

—

Cheat Sheet: Proxy Types

| Type | Direction | Protects Who? | Real World Example |

| Forward Proxy | Internal → Internet | Protects Client | Corporate Office blocking Facebook/YouTube. |

| Reverse Proxy | Internet → Internal | Protects Server | Nginx sitting in front of a Python App. |

| Transparent Proxy | Intercepts Traffic | ISP / Admin | Public Wi-Fi login pages (Captive Portals). |

| SOCKS Proxy | General Purpose | User Identity | Tor Browser, VPN tunneling. |

High Availability

High Availability (HA) means your system is designed to operate continuously without failure for a long time. It removes “Single Points of Failure.“

If you have one server, and it crashes, your website is gone. If you have two servers, and one crashes, the other takes over. That is HA.

- Failover: The plane has two engines. If Engine 1 fails, the plane doesn’t fall; Engine 2 automatically takes the load.

- Active-Passive: A Pilot and a Co-Pilot. The Pilot flies (Active). The Co-Pilot watches (Passive). If the Pilot faints, the Co-Pilot grabs the controls immediately.

- Active-Active: Two construction workers lifting a heavy beam together. Both are working. If one leaves, the other struggles but keeps holding it (if he is strong enough).

1. Failover

Failover is the process of switching to a backup system.

- Manual Failover: An engineer gets a call at 3 AM, wakes up, and changes the DNS record. (Bad).

- Automatic Failover: The system detects the crash and switches instantly. (Good).

2. Active-Active vs. Active-Passive

This is the most common architecture decision you will make.

| Mode | How it works | Pros | Cons |

| Active-Passive | Node A is working. Node B is sleeping (Standby). | Simpler. No data sync issues (usually). | Waste of money. You pay for Node B, but it does nothing until A breaks. |

| Active-Active | Node A and Node B are both taking traffic. | Performance. You use 100% of your hardware. | Complex. If A writes to DB and B writes to DB at the same time, you get conflicts. |

3. VRRP / HSRP: Virtual Router Redundancy

- Context: Your laptop has one “Default Gateway” IP (e.g.,

192.168.1.1). What happens if that Router burns out? Your laptop loses internet. It doesn’t know how to switch to Router 2. - The Solution: VRRP (Open Standard) or HSRP (Cisco Proprietary).

- How it works:

- Router A (Master) and Router B (Backup) talk to each other.

- They create a “Virtual IP” (VIP) like

192.168.1.1. - Router A “holds” the VIP.

- If Router A dies, Router B detects the silence and grabs the VIP.

- Your laptop never knows the hardware changed. It just keeps talking to

192.168.1.1.

—

Health Checks

A Health Check is a question the Load Balancer asks the Server: “Are you okay?”

Types of Checks:

- L3 Check (Ping): “Is the server ON?”

- Flaw: The server might be ON, but the App crashed.

- L4 Check (Port Connection): “Is Port 80 Open?”

- Flaw: Nginx might be running (Port 80 open), but returning “500 Internal Error”.

- L7 Check (Application Logic – Best Practice):

- The Load Balancer requests a specific URL, e.g.,

/health. - The App runs a self-test (checks DB connection, Redis connection) and replies

200 OK. - If the App replies

500or takes too long, the LB marks it Unhealthy.

- The Load Balancer requests a specific URL, e.g.,

Configuration Parameters:

- Interval: How often to check? (e.g., Every 5 seconds).

- Timeout: How long to wait for a reply? (e.g., 2 seconds).

- Healthy Threshold: How many “Successes” before we trust the server again? (e.g., 2 successes).

- Unhealthy Threshold: How many “Fails” before we kill the server? (e.g., 3 fails).

—

Cheat Sheet: HA Terminology

| Term | Meaning | Example |

| Failover | Switching to backup. | Generator turning on when electricity goes. |

| Failback | Switching back to primary when it’s fixed. | Turning off generator when electricity returns. |

| Redundancy | Having extra components. | Carrying a spare tyre. |

| SPOF | Single Point of Failure. | Having only one key to your house. |

| VIP | Virtual IP Address. | A floating IP that moves between routers. |

| Heartbeat | Signal between nodes. | “I am alive… I am alive…” |

Video to learn more about networking.